In the quiet expanse of Romania’s Retezat National Park, a team of paleontologists had been digging for weeks without much success. The sediment layers seemed exhausted of their secrets; only plant fragments and tiny fish bones emerged. Then, unexpectedly, a junior researcher’s pick scraped against something strange: a lightweight but sturdy bone, hollow inside.

The size stunned everyone as it was longer than a human forearm. Little did they know that this discovery would reshape what science thought possible about prehistoric skies. According to Nature 2013, this bone belonged to a creature that once ruled the island with terrifying might.

Introducing Hatzegopteryx thambema

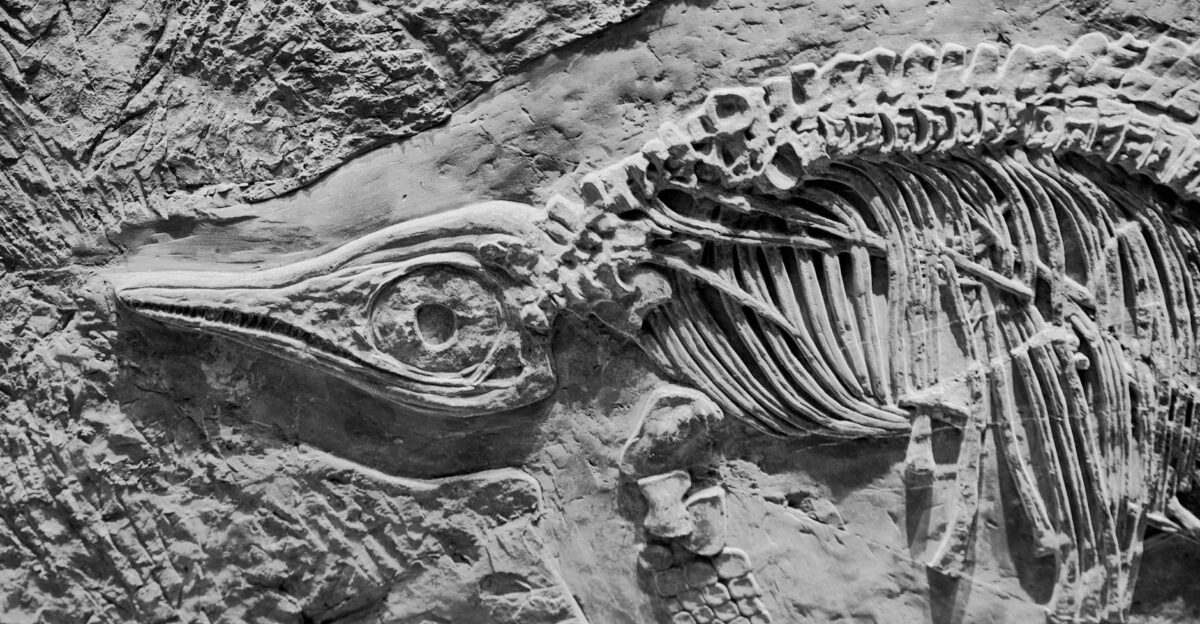

This giant belonged to Hatzegopteryx thambema, a colossal pterosaur whose wingspan rivaled a small plane. Unearthed in the Late Cretaceous limestone beds of the Hațeg Basin, it was unlike any flying reptile previously imagined.

Paleontologist Darren Naish, a leading expert on pterosaurs, described the find in Scientific Reports 2013 as one that “fundamentally reshapes our view of Late Cretaceous island ecosystems.” Hatzegopteryx was not just big; it was a dominant apex predator, towering over most land animals of its time.

A Subtropical Island Lost in Time

Sixty-six million years ago, modern-day Romania was a subtropical island called Hațeg Island. Surrounded by warm, shallow seas, it was a closed ecological system with its own evolutionary rules. According to Zoltán Csiki-Sava of the University of Bucharest, isolation on the island led to “island dwarfism,” where many dinosaurs shrank due to scarce resources.

Without giant theropods prowling the land, an ecological vacuum opened … a gap soon filled by a predator unlike any other.

When the Skies Held the Throne

On Hațeg Island, the dominant predator was not a giant carnivorous dinosaur but a massive flying reptile. Hatzegopteryx’s enormous size and reinforced skeletal structure allowed it to hunt on land, striking terror into dwarf sauropods and primitive mammals alike.

This predator’s reign highlights an unusual twist in evolution—one in which a creature of the skies displaced typical ground predators, as Witton and Naish explained in their 2018 study in Paleontology.

Anatomy of a Sky Giant

Standing taller than a giraffe, Hatzegopteryx boasted a wingspan of around 35 feet, making it one of the largest flying animals known. It was almost 10 feet long, and the skull carried a powerful, crushing beak reinforced by dense internal struts – structures rare among flying reptiles.

Paleontologist Mark Witton described it as “built like a tank, yet capable of flight,” capable of delivering powerful strikes with its massive jaws.

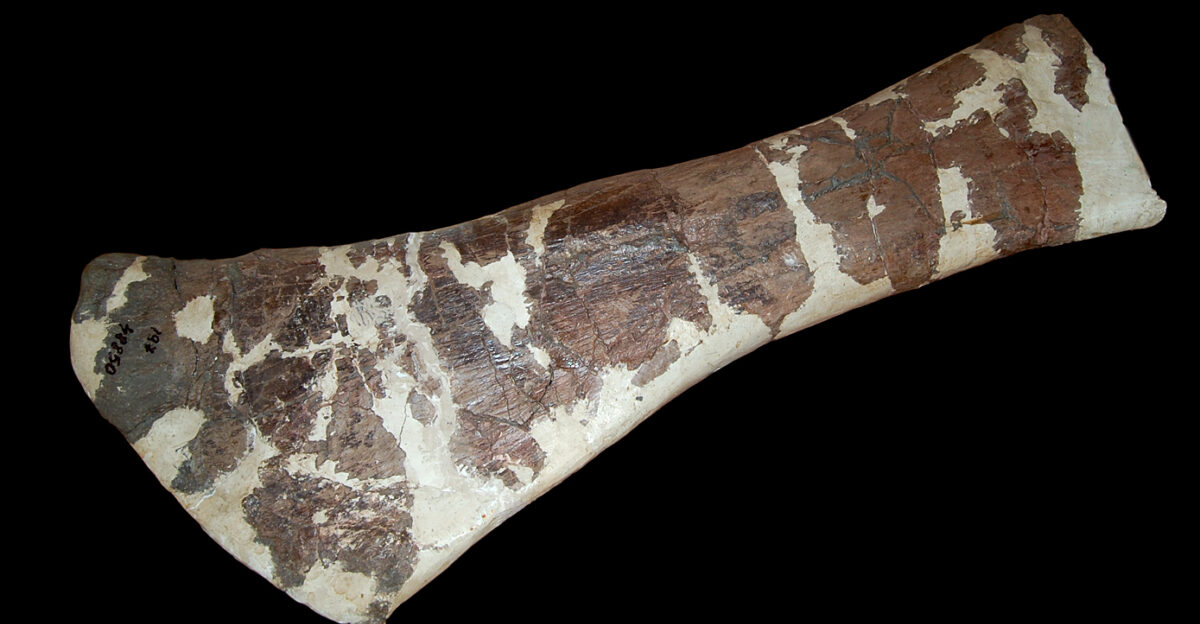

Thick Bones for Brutal Power

Unlike the light, hollow bones typical of most pterosaurs, Hatzegopteryx had thick, dense bones more comparable to land predators. CT scans by researchers at the University of Bucharest revealed reinforced bone walls that could absorb impacts from struggling prey.

This discovery contradicted the longstanding notion that pterosaurs were fragile gliders, showing instead a robust predator designed for strength and endurance.

First Missteps: A Dinosaur in Disguise

When the fossils were first discovered in the early 2000s, scientists mistakenly identified them as belonging to a large theropod dinosaur due to the bone density and size. It was only after microscopic and CT analysis revealed the distinctive hollow internal structure of pterosaur bones that the creature’s true Nature was unveiled.

This revelation astonished paleontologists worldwide, rewriting the ecological roles pterosaurs could fill.

Eyes Made for Hunting

The partial skull reconstruction showed large eye sockets positioned for maximum depth perception – a crucial trait for tracking prey in flight or on land. According to a 2019 report in Scientific American, this adaptation suggests Hatzegopteryx was an efficient hunter with keen vision, able to ambush prey with precise timing.

Its eyes were large relative to its skull, an evolutionary necessity for survival in the complex forest and plains environment of Hațeg Island.

Hunting in the Shadows

Biomechanical models published in PLOS ONE propose that Hatzegopteryx’s short, powerful neck and reinforced beak allowed it to deliver swift, deadly strikes to prey.

Rather than prolonged chases, it relied on ambush tactics, stalking small dinosaurs and mammals before overpowering them with sheer force. It may have used its massive wings to intimidate or herd prey before the final attack.

Apex Predator Without Rivals

On Hațeg Island, the most enormous dinosaurs were dwarves no bigger than modern cows. The absence of substantial carnivorous theropods gave Hatzegopteryx an uncontested reign.

Zoltán Csiki-Sava stated in a 2016 interview with National Geographic that it was “the lion, leopard, and eagle all in one”, a flying apex predator dominating land and air. Its ability to hunt prey almost half its size made it a unique force.

Ecological Impacts of a Sky Ruler

Hatzegopteryx’s dominance forced prey species to adopt new defensive strategies. The dwarf sauropod Magyarosaurus and hadrosaur Telmatosaurus evolved armor and behaviors to evade this aerial hunter.

According to Darren Naish in Nature, this predator exemplifies evolutionary flexibility, revealing how island ecosystems can foster unexpected biological innovations.

Fossil Site Within a Protected National Park

The Hațeg Basin, where these fossils emerged, now lies within Retezat National Park, a UNESCO Global Geopark safeguarding one of Europe’s richest Late Cretaceous fossil deposits. However, erosion and illegal fossil collection threaten this treasure trove.

Researchers like Csiki-Sava emphasize the need for preservation, warning that “every year we lose fossils to natural weathering”.

Technology Unlocking Ancient Secrets

Modern tools—micro-CT scanning, 3D modeling, and biomechanical simulations—have allowed scientists to reconstruct Hatzegopteryx’s anatomy with incredible detail. These methods revealed how strong its bite force was compared to some of the most enormous carnivorous dinosaurs.

Such detailed reconstructions were impossible two decades ago and have opened new doors to understanding extinct species.

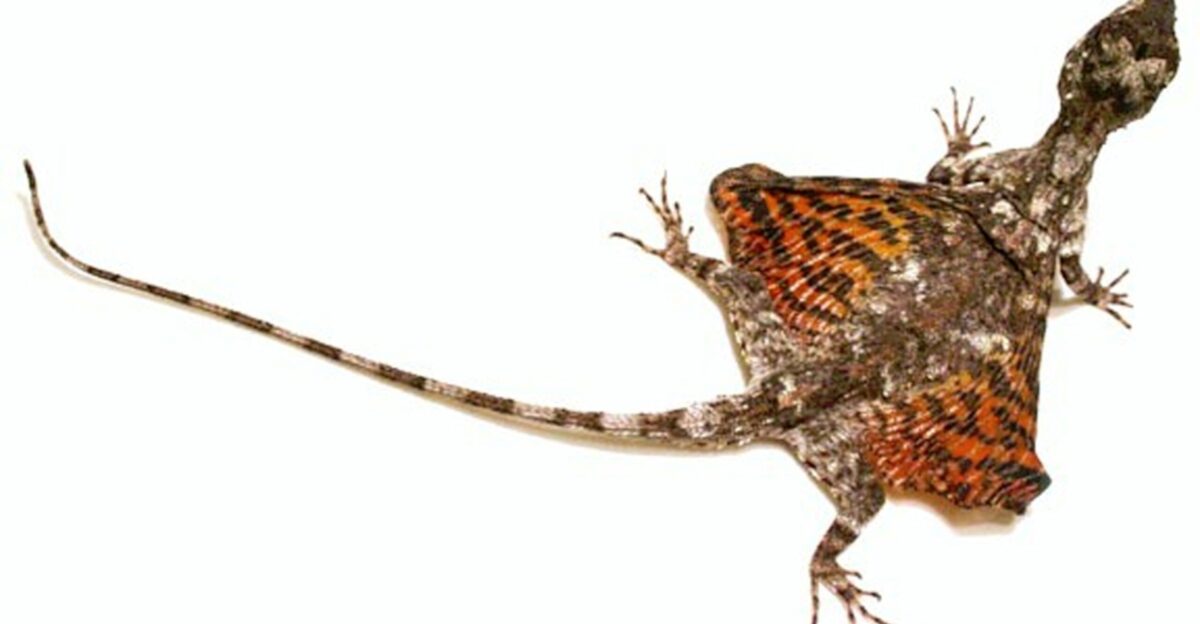

A Terrestrial Hunter in Flight

Unlike relatives like Quetzalcoatlus, known for soaring and scavenging, Hatzegopteryx’s anatomy suggests it was built for short bursts of terrestrial hunting. Its thick bones and powerful musculature supported quick, aggressive attacks on the ground.

Witton and Naish highlighted this insight in a 2017 Royal Society Open Science paper, which challenged previous assumptions about giant pterosaur ecology.

Feeding Behavior Revealed

Fossilized bite marks on small dinosaur bones in the region match the trauma such a predator could inflict. Researchers speculate Hatzegopteryx stalked its prey, striking with its beak and swallowing more minor victims whole, while tearing larger prey into pieces.

This feeding style parallels modern birds like herons and storks on a much grander, deadlier scale.

Debunking Jurassic Myths

Popular culture often portrays pterosaurs as fragile, delicate gliders. The Hațeg discovery shatters this myth. Paleontologist Naish described Hatzegopteryx as “more like a flying bear than a seagull”, reminding us that prehistoric life was stranger and more varied than often depicted.

The reality of such creatures is often more thrilling and terrifying than fiction.

Competitors and Co-inhabitants

Other fauna on Hațeg Island included small, agile theropods that scavenged or preyed on juveniles of larger species. But none matched Hatzegopteryx in size, speed, or predatory dominance.

The giant pterosaur had free rein over the island’s food web without large land-based carnivores to challenge it. In a 2016 National Geographic interview, Csiki-Sava remarked, “In this unique environment, a flying reptile became the lion of its world,” its reign so complete that even terrestrial predators likely scavenged its kills rather than risk a confrontation.

Evolutionary Lessons from Isolation

Hatzegopteryx’s rise shows how isolated ecosystems produce extraordinary adaptations. The island rule, which predicts size shifts in isolated species, allowed a pterosaur to evolve traits usually reserved for ground predators.

This case challenges assumptions about flying reptiles globally and expands our understanding of their ecological roles.

The Legacy and Ongoing Mystery

Despite partial fossil remains – mostly skull and wing fragments – scientists continue to search for more complete specimens.

Questions linger: How long did it spend flying? Did it have social behaviors? The hunt for answers drives ongoing excavations in Retezat National Park, blending fieldwork with cutting-edge technology.

A Testament to Discovery

The colossal silhouette of Hatzegopteryx, ruling air and land, reminds us of evolution’s limitless creativity. According to Csiki-Sava, “We still live in an age of discovery where the past surprises us.”

The Hațeg Basin remains a vital window into ancient life, and its fossils continue to rewrite the story of prehistoric Earth.