In 1955, a fossil fan named Francis Tully searched through leftovers from a coal mine near Braidwood, Illinois.

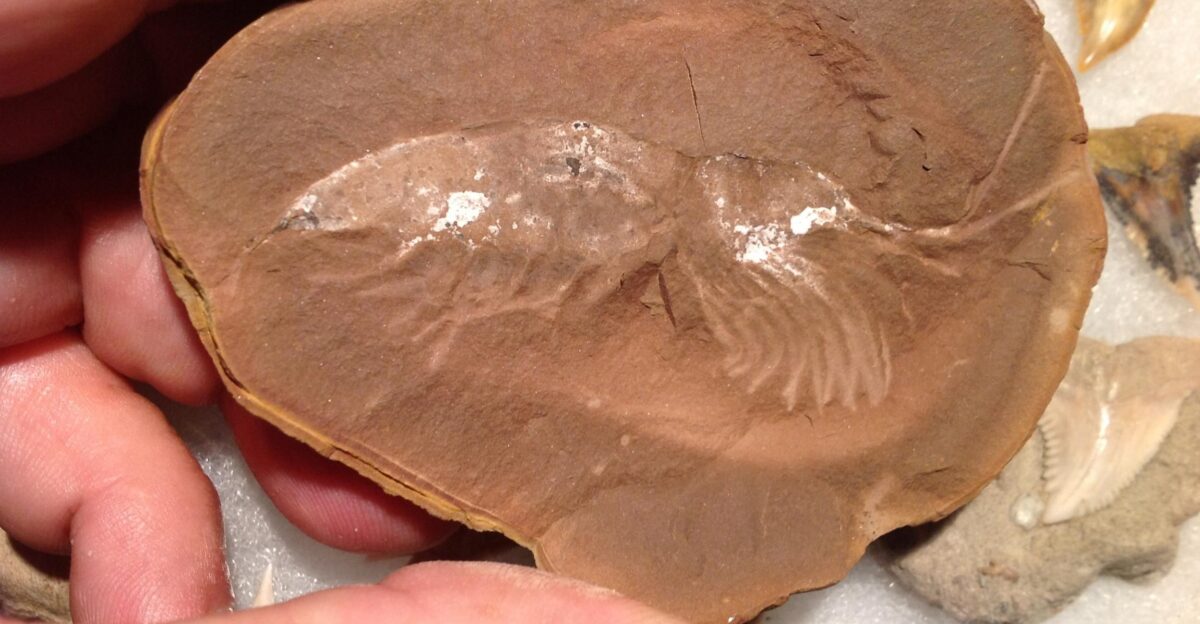

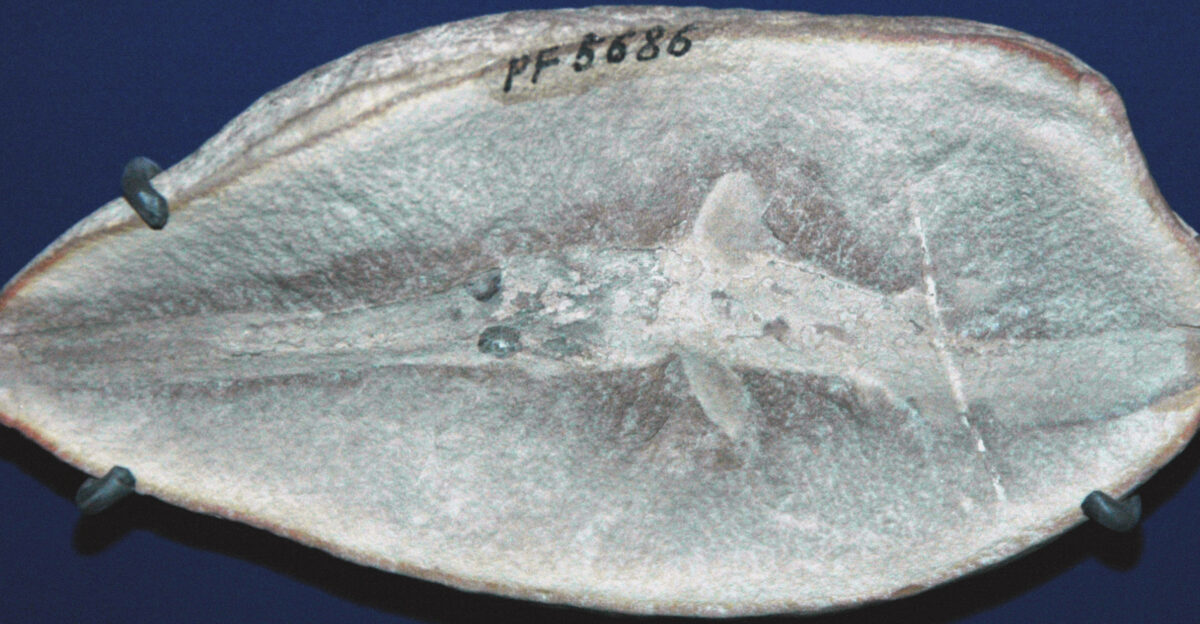

He found a 300-million-year-old rock and broke it open to discover something strange inside, a fossil of a weird animal with a long nose, eyes on stalks, and a body shaped like a torpedo.

Tully showed it to scientists at Chicago’s Field Museum, but they couldn’t figure out what it was either. They called it the “Tully Monster.”

Coal Country

The Mazon Creek fossil site is about 65 miles southwest of Chicago. In the 1800s, people started mining coal, which accidentally turned the area into a goldmine for fossils.

French explorers found coal nearby in 1673, but significant mining operations didn’t take off until around 1810 and continued until the 1970s.

In the 1920s, massive strip mines dug up layers of rock called the Francis Creek Shale, which contained fossil-rich rocks.

These mining activities were meant to extract coal, but exposed many fossils from the ancient forests that produced it.

Ancient Illinois

Three hundred million years ago, Illinois looked completely different from today. It was much closer to the equator and covered with hot, steamy swamps, river deltas, and shallow bays.

Huge, tropical forests filled the area, with giant plants like lycopsids, massive horsetails, seed ferns, and early conifers.

The air had lots of oxygen, and the warm, wet climate allowed many kinds of animals to live there, including early amphibians, bugs, sea animals, and soft-bodied creatures.

All of this existed as the giant supercontinent called Pangaea was forming.

Perfect Preservation

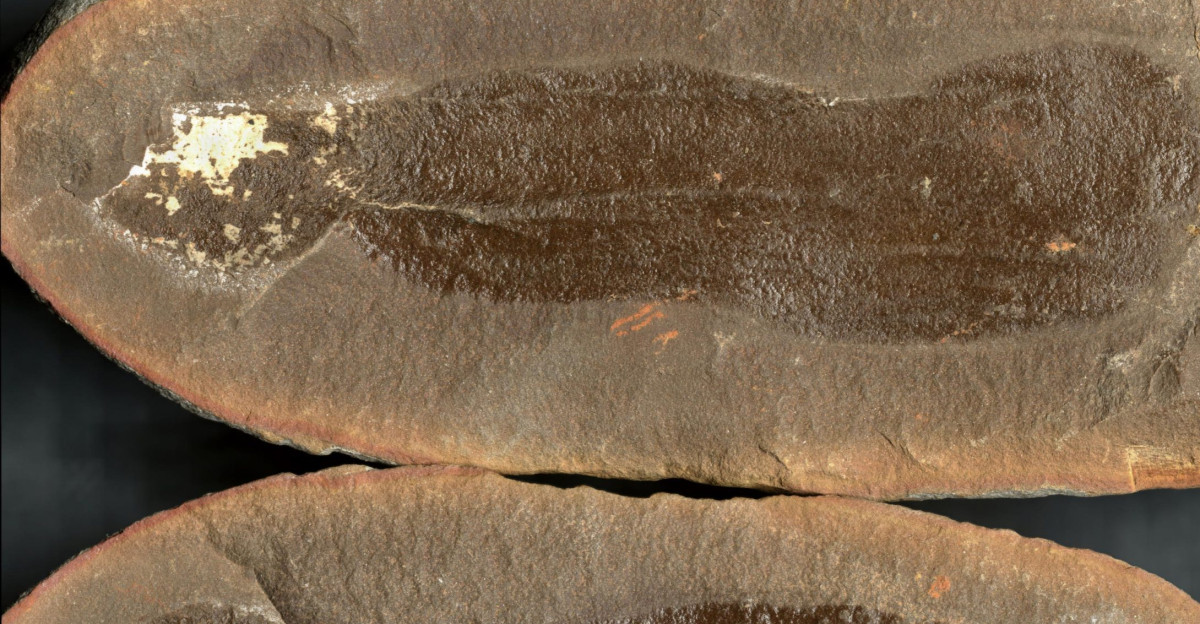

The remarkable fossil preservation at Mazon Creek happened because of a special natural process.

When plants or animals died in the ancient swampy area, fine mud quickly covered them before anything could eat or break them down. As the remains broke down, bacteria produced carbon dioxide mixed with iron in the water.

This created a mineral called siderite, forming a hard shell around the dead creature or plant. This happened very fast, so even soft parts were protected before they could rot away.

These hard, iron-rich nodules acted like natural time capsules, keeping the fossils safe and well-preserved for over 309 million years.

Three Lost Worlds

Researchers at the University of Missouri have found that the Mazon Creek fossil site has fossils from three different ancient environments, not just two as people thought.

They looked at almost 300,000 fossil rocks from 350 places. One environment was near the shore, containing land plants and freshwater animals. The other two were ocean environments: one had mostly animals living on the sea floor, like worms and clams, and the other had many jellyfish-like creatures.

Lead researcher Jim Schiffbauer explains: “We found three readily identifiable paleoenvironments, including the unique characteristics of a benthic marine assemblage representing a transitional habitat between the nearshore and offshore zones.”

Living Laboratory

The Field Museum in Chicago has the world’s most critical Mazon Creek fossil collection, with more than 20,000 fossil-filled rocks that scientists use for research.

Assistant Curator Arjan Mann calls Mazon Creek “one of the greatest fossil localities in the world, right outside the Chicago area,” showing how important it is to science everywhere.

The collection results from many years of teamwork between scientists and amateur fossil hunters, who searched mines, piles of rock, and natural spots across northeastern Illinois for these fossils.

Nowadays, Mazon Creek fossils are sent to museums worldwide, so, as Mann says, “if you go about just to every museum collection in the world, you can find Mazon Creek fossils.”

Fossil Jackpot

The vast variety of fossils found at Mazon Creek shows why it’s called a “fossil jackpot.” Scientists have seen over 800 kinds of fossils there, from tiny life forms to big amphibians.

The fossils include everything from jellyfish and sea anemones to giant millipedes, early insects, and many different types of plants, such as ferns, seed ferns, and huge lycopsids.

The fossils’ well-preserved condition lets scientists study how different plants and animals lived together and see what complete food webs looked like when animals were first becoming the main creatures on land.

Scientific Goldmine

Scientists consider Mazon Creek to have the best and most complete record of life in the ancient Paleozoic era.

It shows us what happened when rising seas flooded the old coal swamps. The fossils found here do more than add up to a long list; they show how animals behaved, who ate whom, and preserve fine details that usually disappear over time.

Researchers have used these fossils to learn how the first backboned animals evolved, what the climate and air were long ago, what kinds of trees and plants grew, and what the chemistry of the ancient oceans was.

Global Significance

The Mazon Creek fossil site became a National Historic Landmark in 1997 because it is essential in studying ancient life. Fossils from Mazon Creek are shown in famous museums worldwide, including the Smithsonian and many European museums.

Scientists have written hundreds of research papers about these fossils, covering how life evolved and changes in the ancient Earth’s chemistry. Discoveries keep being made from these fossils.

Mazon Creek has helped scientists understand the Carboniferous Period and has provided important clues about the evolution of major animal groups, such as early insects, crustaceans, and the first animals that started to live on land.

Microscopic Mysteries

Thanks to new technology, scientists can see inside Mazon Creek fossils without opening or damaging them. At the University of Missouri, experts use special X-ray machines and advanced imaging tools to examine the 3D shapes of fossils hidden inside rocks.

This has helped them discover new details about fossilized plants and animals that were not visible before and learn more about the chemistry that helped preserve these fossils so well.

By combining these modern techniques with fossil collections gathered long ago, scientists are making exciting discoveries about ancient life.

Mining Legacy

The coal mining that uncovered the Mazon Creek fossils is essential to Illinois’s industrial history. At first, mining in the 1800s was small, but by the 1900s, it grew much bigger with massive strip mines.

The rock layer called the Francis Creek Shale, which holds the fossils, was initially thought to be useless and was just dumped on top of piles after miners took out the coal underneath.

But in the 1850s, fossil collectors realized these rocks were full of valuable fossils, so they started searching through the mine dumps. This shows how mining for coal accidentally helped scientists find and study the fossilized plants and animals that once formed the coal.

Collector Collaboration

The Earth Science Club of Northern Illinois is an excellent example of amateur fossil hunters and professional scientists working together to study Mazon Creek.

Club members team up with Field Museum experts by going on organized fossil-hunting trips, sometimes on public or private land with the owner’s permission. These amateur collectors spend thousands of hours each year cleaning fossils, entering information into databases, helping to identify specimens, and teaching others about fossils.

Many important fossil finds have been made because club members find rare or interesting specimens and donate them to museums instead of keeping them for themselves. They know how vital these fossils are for scientific research and learning.

Basement Freezers

Amateur fossil collectors have devised clever ways to open Mazon Creek rocks without breaking the fossils inside. Many people use their home freezers for this. The best method is to keep freezing and thawing the fossil rocks in water.

The ice slowly cracks the rocks along natural lines, instead of smashing them open with a hammer, which could ruin the fossils. Rich Holm, who started as a software engineer but now collects fossils, explains: “It’s a passion that grows exponentially. So, probably very soon after you start, you need your freezer.”

This process takes a long time, sometimes six months to a year, for each fossil. Collectors often rotate many containers through their freezers, checking the rocks every few days, turning the whole thing into an ongoing, year-round treasure hunt.

Research Renaissance

Thanks to Assistant Curator Arjan Mann, the Field Museum in Chicago again focuses on studying Mazon Creek fossils. After curator Eugene Richardson passed away in 1983, the museum started paying more attention to dinosaurs and less to Mazon Creek.

Mann is now working to rebuild partnerships with amateur fossil hunters and increase careful research on the museum’s fossil collection.

His team is especially interested in big questions, like how ancient amphibians changed over time into the ones we see today. They use Mazon Creek fossils to preserve features that don’t appear elsewhere.

This new effort shows how the museum can change its focus over time, while still respecting and building on the work of earlier collectors and scientists.

Future Discoveries

Scientists believe that Mazon Creek will continue to provide amazing scientific discoveries, especially as new technology and digital tools make it easier for researchers worldwide to study the fossils.

Current research looks at how the climate changed during the Carboniferous period, using Mazon Creek fossils to learn how ancient plants and animals reacted to rising sea levels and atmospheric changes.

This work is important today because it helps scientists predict how today’s plants and animals might respond to ongoing climate change.

Cutting-Edge Analysis

New high-tech methods are changing how scientists study Mazon Creek fossils. Experts now use powerful X-rays, chemical tests, and even ways to look for ancient molecules in the fossils.

For example, scientists can measure mercury in the fossils to determine what different animals ate, or use special chemistry to find traces of the original organic material.

By combining old-fashioned fossil study with these new techniques, scientists are discovering completely new information in fossil collections over a hundred years old.

Educational Impact

Mazon Creek is a great educational tool because it helps students and the public understand Earth’s ancient history by letting them see and touch actual fossils.

At the Field Museum, visitors can handle real fossils and learn how scientists do their research. Schools work with the museum so students can meet real paleontologists and learn directly from them.

These hands-on experiences help people understand evolution, geology, and environmental science and can inspire young people to become scientists.

Social Media Science

Mazon Creek fossils have become very popular on social media, where collectors worldwide show off their finds and talk to each other. However, this online attention has also led to confusion and false information about the proper way to collect fossils and who is allowed to collect at specific sites.

Because of this, scientists and serious collectors use social media to teach people the right way to collect fossils and explain the rules that protect these critical sites. Real paleontologists get involved online to help people understand the difference between collecting fossils responsibly and digging to sell rare fossils.

The internet has made it easier for scientists and collectors to collaborate. Still, it also brings new problems, making controlling who visits and collects at these special fossil locations harder.

Historical Precedent

The way people collect fossils at Mazon Creek has inspired similar efforts all over the world. At Mazon Creek, amateur fossil hunters and professional scientists work together, showing that hobbyists can help science instead of competing with researchers.

Other famous fossil sites, like the Burgess Shale in Canada and the Solnhofen Limestone in Germany, have also started using some of these ideas.

The history of Mazon Creek shows that even industries like mining can lead to significant scientific discoveries. It also proves the importance of keeping fossil sites open for research and education for professionals and everyone interested.

The teamwork between museums and the community at Mazon Creek has become a model used worldwide for fossil collecting and building partnerships between the public and scientists.

Ancient Lessons

The Mazon Creek fossil site shows that long ago, Illinois was home to some of Earth’s most varied and rich ancient ecosystems. This site holds fossils from three different environments, showing how complex life was 309 million years ago during the Carboniferous period.

Rapid environmental changes, as the giant supercontinent Pangaea formed, helped preserve all kinds of life in fantastic detail.

These fossils exist today thanks to teams of scientists and amateur fossil hunters working together.