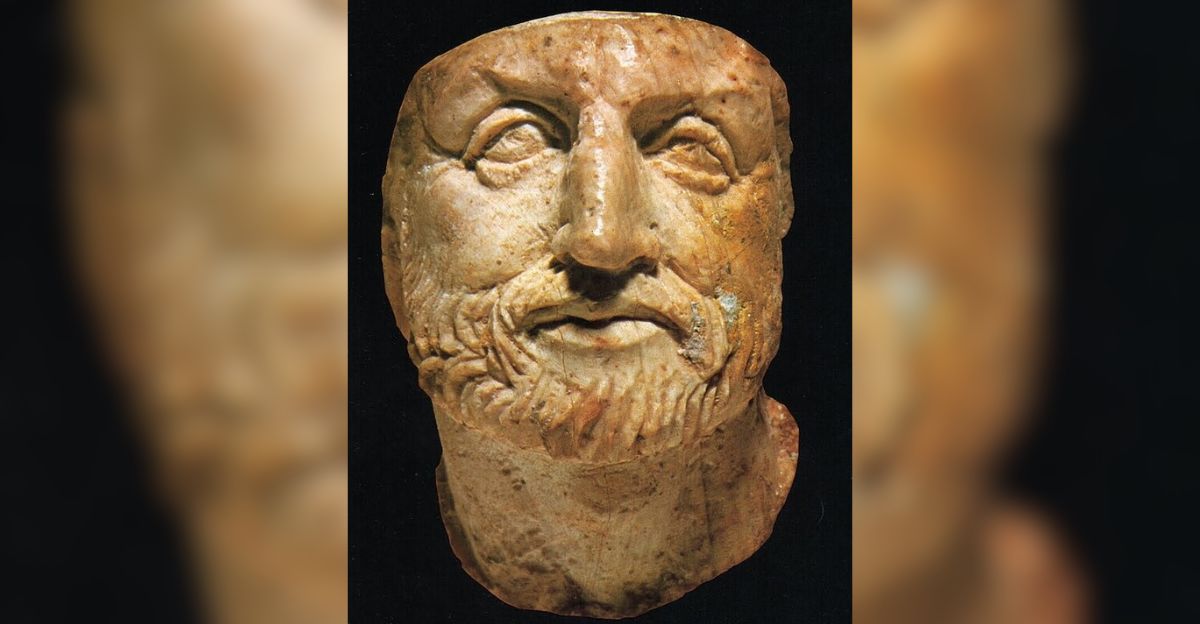

For decades, scholars believed that the magnificent tomb at Vergina was the final resting place of Philip II, the one-eyed father of Alexander the Great. Golden artifacts, warrior gear, and ceremonial objects all implied a royal burial.

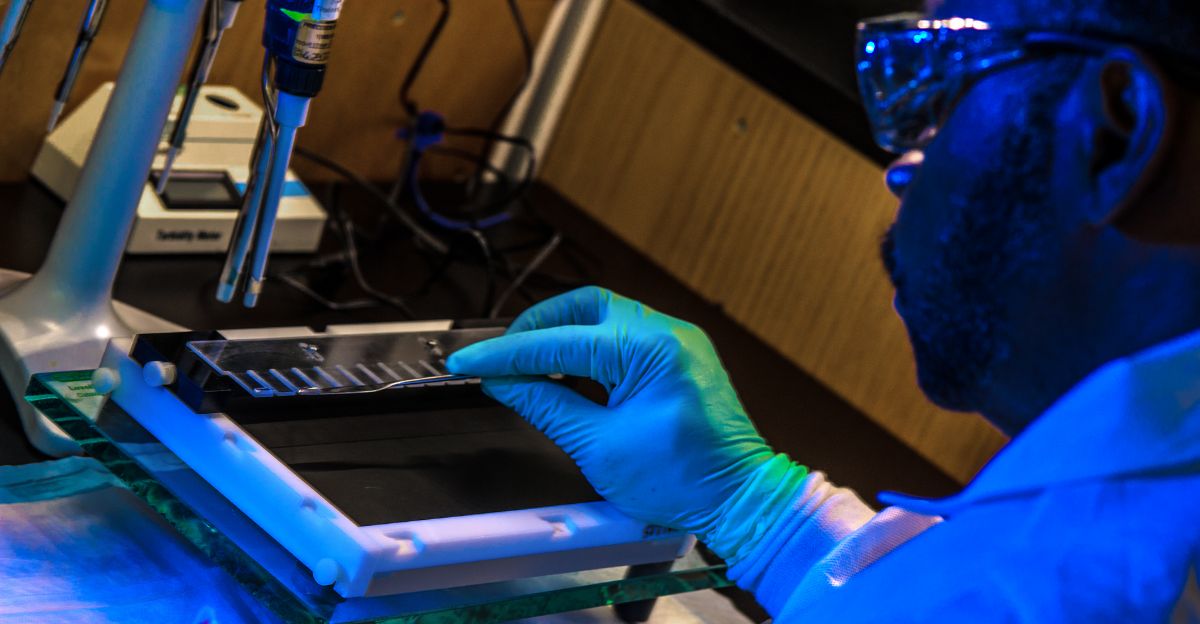

But recent scientific evidence has belied this long-standing narrative. New DNA, radiocarbon, and forensic tests suggest the tomb may not contain Philip II but rather that of something else—several people in fact.

The news has archaeologists scrambling to revise historic timelines and reconsider our approach to identifying ancient monarchs. The implications aren’t merely academic; they rewrite royal history from scratch.

The Wrong Royal in the Right Tomb?

When Manolis Andronikos unearthed Tomb II at Vergina in 1977, he was certain that he had Philip II. A gold larnax with the Macedonian sunburst, a diadem, and weaponry were all in order. Further, a fractured leg bone on the male skeleton corresponded with Philip’s recorded war injuries.

Even with these circumstantial clues, however, no incontrovertible proof linked the remains to Philip. As archaeology advanced, the seeds of doubt were sown. The objects found were befitting a king, but which king?

Now, modern technology is providing the answers to rising questions, revealing a story concealed not only in objects, but in the genetic code of the dead.

Could It Be Philip III Arrhidaeus Instead?

Some experts argue that the tomb holds Philip III Arrhidaeus, Alexander’s half-brother and a puppet king placed on the throne after the conqueror’s death.

Firstly, Arrhidaeus fits the tomb’s timeline better than Philip II: he died in 317 BCE, was of royal blood, and his burial was reportedly elaborate. But there’s some skepticism of even this theory: historical accounts say his body was exhumed and reburied multiple times amid political chaos.

Could the inconsistencies in the skeleton’s age, injury profile, and burial context point to this unstable figure? If true, the tomb still holds a king, just one not revered in textbooks.

Macedonian Tomb Politics: Identity as Propaganda

Royal tombs serve both the living and the dead. To assert that a tomb was that of Philip II in 1977 was politically powerful as it linked modern Greece with Alexander the Great’s ancestry during a time of regional nationalism.

The Greek government marketed the discovery widely. But this archaeopolitics created blind spots. Scientific skepticism was swept under the rug in favor of a good story, and the urge to anchor modern identity in old glory led to hasty conclusions.

In this way, tombs become arenas, not just of archaeology, but of ideology, where DNA analysis is as politicized as border claims or UN declarations of cultural ownership.

Can AI Solve the Secrets of Ancient Tombs?

Artificial intelligence (AI) might just become the next big tool in tomb archaeology. Mainly because AI would be capable of examining bone structure information, predicting familial connections, reconstructing facial features, and matching skeletal markers with historical texts.

By feeding machine learning algorithms DNA sequences and osteological abstracts, researchers could rapidly test hypotheses about royal dynasties. Imagine a neural network knowledgeable about every known Hellenistic tomb.

Would it correctly identify who is in Tomb I? The blend of new technology and ancient bones might be disturbing, but it brings accuracy to a science defined by ambiguity. Even Alexander might marvel at algorithmic successors to divine prophecy.

DNA Testing and the Death of Certainty

In 2023, scientists revisited the remains found in Tomb I using mitochondrial DNA testing and radiocarbon dating. Much to their dismay, the tests revealed that the tomb may contain not Philip II but a younger man, a woman, and even six Roman-era infants.

Moreover, Tomb I’s offerings and architecture were found to be fairly simple, not including rich regalia and sophisticated stonework and multi-roomed layout due a Macedonian king.

Tomb I’s minimalism and lack of ceremonial markers suggest it belonged to a lesser aristocrat, not a king. In science, DNA rarely lies, and here it revealed centuries of myth constructed upon historical guesswork.

A Young Man Vs an Elderly King

As a further surprise, scientists discovered that the male skeleton was dated to someone who died between 420 and 370 BCE—decades prior to the assassination of Philip II in 336 BCE. In fact, the skeleton belonged to a man in his early30s, far too young to be the septuagenarian king.

Furthermore, the skeletal characteristics failed to replicate Philip’s reputed war wounds, his damaged right eye socket and leg wounds in particular. The male skull was intact, with no orbital damage at all, and there was also no sign of the leg wound historians attributed to Phillip.

The Queen Beside the King—Or Not?

The female found in Tomb I, buried beside the male, was aged 18–25. Her identity cannot be ascertained, but she had some significance. Wives, daughters, or ritual priestesses were typically buried in royal tombs.

She was likely of noble birth, according to the funerary objects beside her. Nevertheless, no written record exists of a woman dying with Philip, and her skeletal examination shows no trauma consistent with ritual sacrifice.

Was she his wife, his concubine, or some completely unrelated member of the elite? Now, her presence defies conventional assumptions regarding burial practices, gender, and Macedonian royal succession.

Six Infants, Six Centuries Later

Most surprising is the discovery of six infant skeletons buried later in the tomb—in Roman times, centuries after the first burial. Radiocarbon dating places the infants at 150 BCE to 130 CE, long after Alexander’s dynasty collapsed.

This reuse of royal tombs wasn’t uncommon but raises more questions. Were these children of nobility, sacrifices, or regular people buried in a position of honor? Their inclusion suggests the tomb’s symbolic power outlived its initial function.

The dead rest ill at ease here—monarchy and babies of different eras heaped in a single old mausoleum, interwoven across generations in both flesh and political memory.

What Lies Beneath the Royal Narrative

This new information on the tomb challenges us to move on from old narratives about history. We like to imagine it as linear, as names and dates in a neat row, but the dead’s final resting places often tell us messier stories.

The presence of Roman-period children, a young woman, and a younger man upends the neat biography of Philip II. Tombs are not time capsules so much as manuscripts, rewritten by new generations, politics, and the mythological afterlife.

This tomb used to be the center of royal propaganda and is now a forensic crime scene demanding scientific objectivity.

History’s Skeleton in the Closet Revealed

The tomb at Vergina is a reminder of how easily stories turn into beliefs. For generations, textbooks, museums, and patriotic pride relied on the assumption Philip II lay beneath that golden larnax.

But reality is more complex. A young man, a mysterious woman, six children from another time are the true inhabitants, haunting our history. This newest discovery becomes significant as we dig into the past, confronting the limits of our understanding.

While this grave doesn’t house a king, it’s provided us with history’s truth. Now many beg the question: where does the king lie?