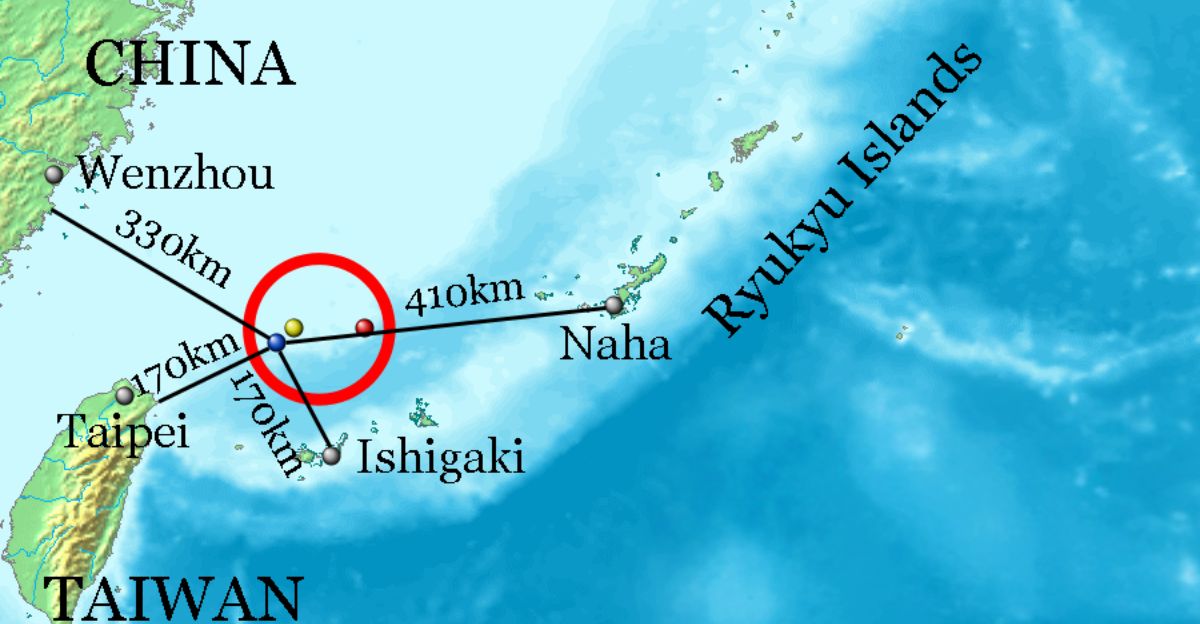

Scientists from the National Museum of Nature and Science in Tokyo have re-enacted an epic and ancient Paleolithic voyage. In 2019, they carved a 25-foot canoe (“Sugime”) from cedar using only stone-age tools, then launched it from Taiwan. Guided only by the sun, stars, and ocean swells (no modern navigation instruments were used), five paddlers (one woman and four men) survived a grueling 45-hour journey through the dangerous and powerful Kuroshio current to reach Yonaguni Island.

This 140-mile crossing – mirroring a route taken about 30,000 years ago – provides truly striking new evidence about their ancestors’ seafaring capabilities.

Why Scientists Tested the 140-Mile Route

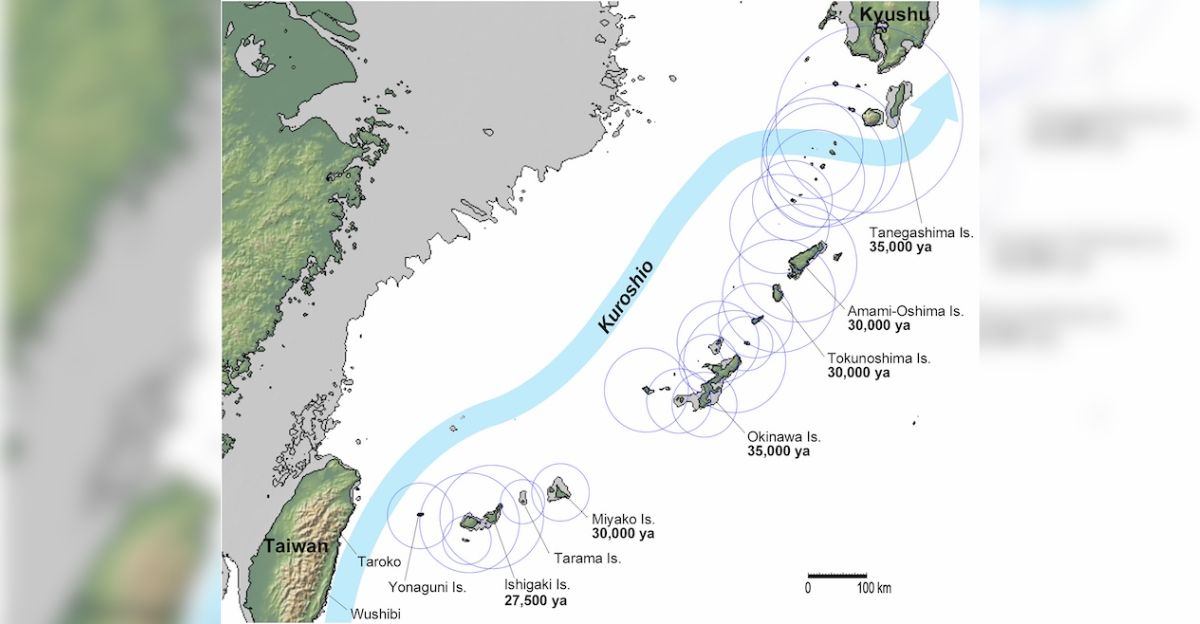

Researchers wanted to solve a long-standing mystery: early modern humans clearly reached Japan’s Ryukyu Islands from Taiwan around 30,000 years ago, but it was unclear how they managed the open-ocean leg. Project leader Professor Yousuke Kaifu (University of Tokyo) explains the team began with simple questions – “How did Paleolithic people arrive at such remote islands as Okinawa? … What tools and strategies did they use?”.

He notes that archaeological fragments alone leave huge gaps (“the nature of the sea is that it washes such things away”), so the team turned to experimental archaeology.

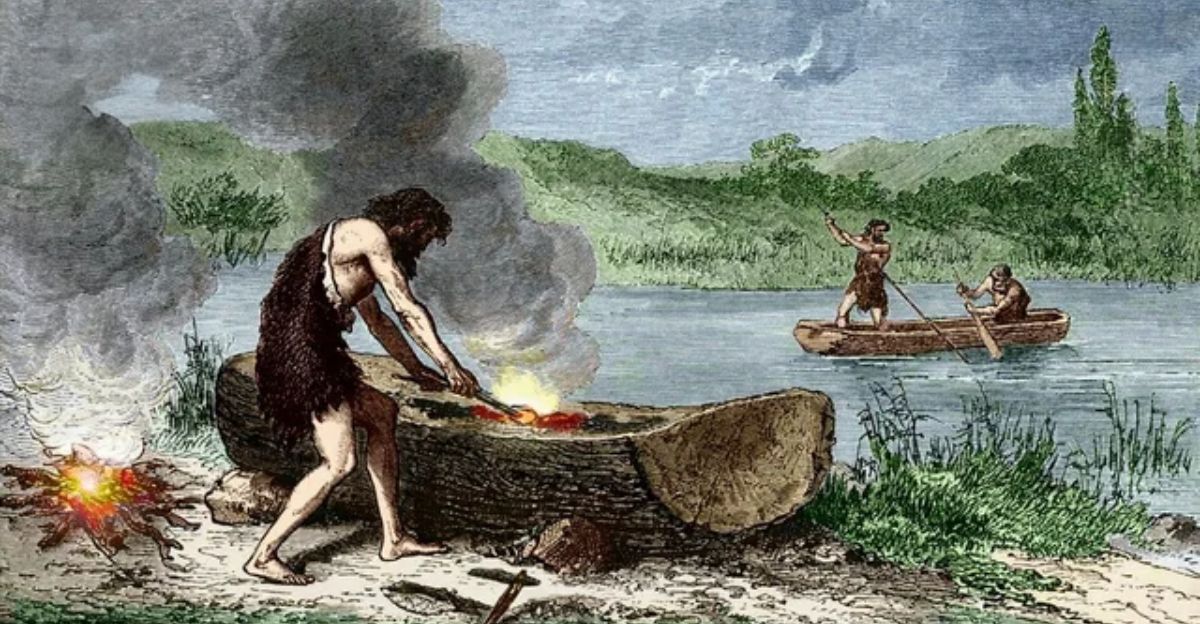

Crafting a Canoe with Prehistoric Tools

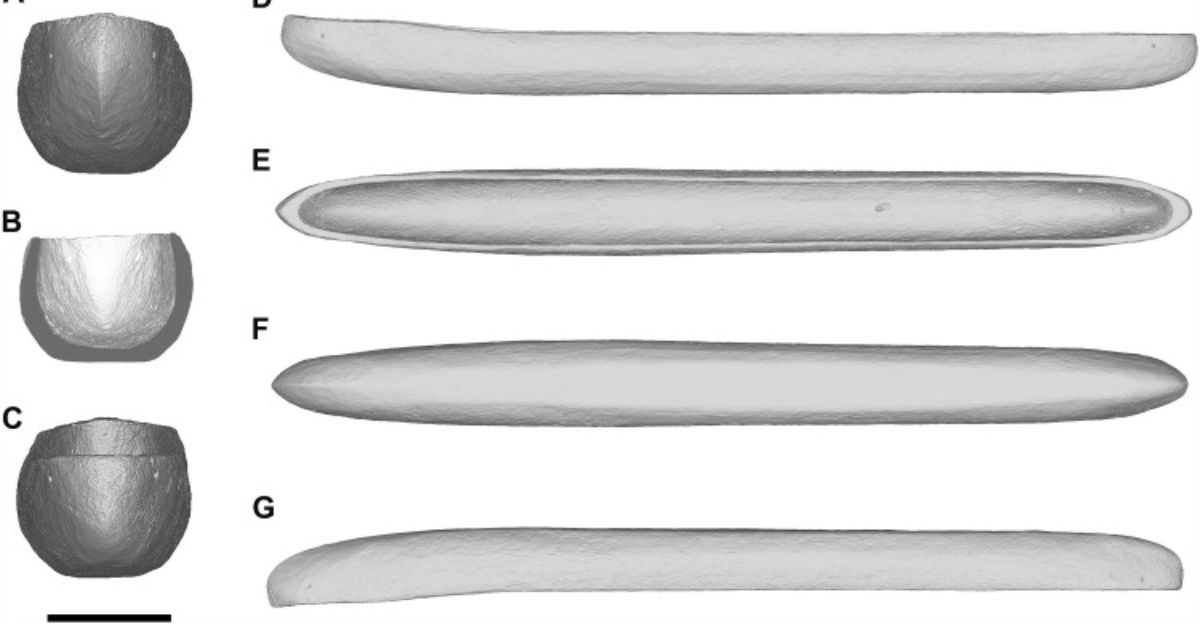

The scientists first tested different boat designs. They tried flimsy reed and bamboo rafts, but simulations and scale trials showed those craft could not survive the Kuroshio. Instead, they settled on a dugout canoe. Using replica Stone Age adzes and axes, the team hewed a 7.5‑meter cedar log into the dugout canoe “Sugime”.

Early trials of the raw log showed it would capsize, so the crew burned and polished parts of the hull to improve stability.

Paddling 45 Hours Through the Kuroshio Current

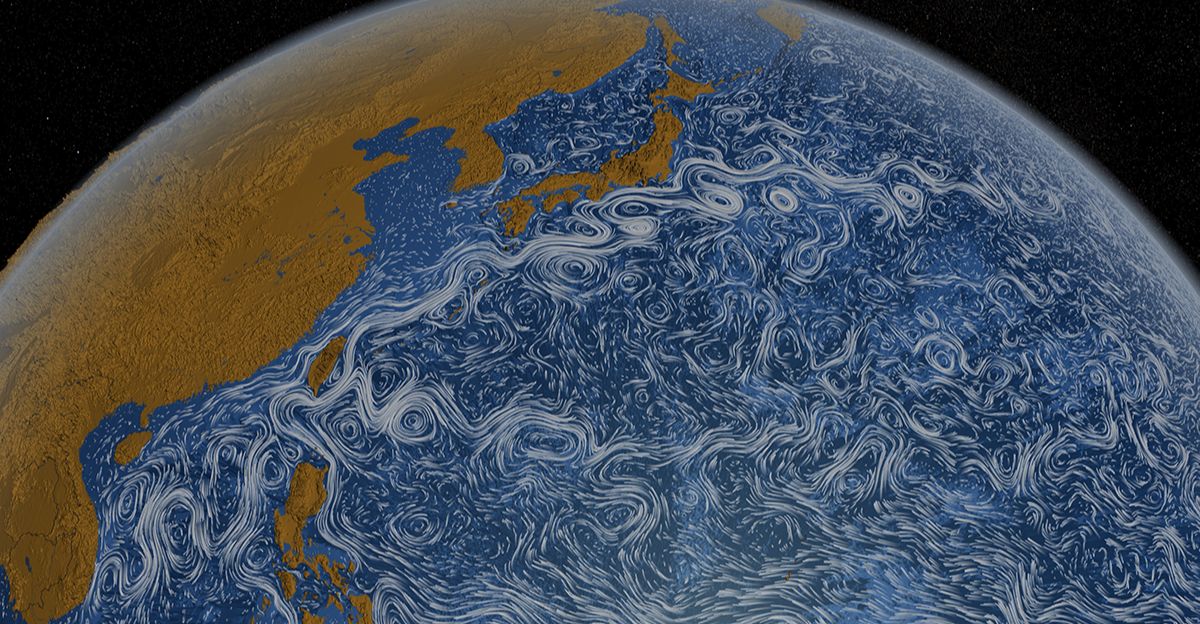

With the canoe prepared, five team members set off for Yonaguni Island. Over roughly 45 hours and 140 miles of open sea, they navigated without any modern aids – no compass or map – steering only by the sun, stars and swells. The paddlers took short breaks (letting Sugime drift) when fatigue set in, but ultimately completed the crossing safely.

It was a physically punishing trip: Kaifu says the project “gave us a deep respect for our Paleolithic ancestors,” who risked being swept far from home on each foray. In fact, Kaifu notes, the voyage confirmed that only highly skilled paddlers could have done this, facing a current so strong that even experts thought “you could only drift aimlessly” if caught in it.

Revealing the Skills of Early Mariners

This hands-on experiment exposed details of ancient craftsmanship and expertise that archaeology alone can’t show. Maritime archaeologist Helen Farr observes that such test voyages reveal a “level of skill and planning that is really hard to see in the archaeological record”. By carving and steering the canoe, the team glimpsed those hidden “human details” – discipline, navigation and strategy – of Pleistocene seafaring.

Kaifu emphasizes that the journey demanded expert paddlers: the Stone Age sailors “must have all been experienced paddlers with effective strategies and a strong will to explore the unknown”.

Computer Models Confirm Canoe Strategy

On land, the researchers backed up their voyage with computer simulations. They confirmed that a dugout canoe (not a flimsy raft) was necessary to beat the current. By running hundreds of virtual crossings under different seasons, launch sites and rowing strategies, they showed the Kuroshio could be navigated under the right conditions.

For instance, launching from northern Taiwan in summer and steering slightly southeast maximized the eastward drift.

New Insights on Early Human Migration

The experiment reshapes our understanding of Pacific migrations. Archaeological evidence already indicated people reached the Ryukyus ~30,000 years ago, but how without boats or navigational charts? Now we have a scenario supported by data and demonstration.

Kaifu points out that, unlike Heyerdahl’s speculative Kon‑Tiki, today’s teams can ground their voyages in actual evidence: “Compared to the time of the Kon‑Tiki, we have more archaeological … evidence to build realistic models”. The canoe crossing confirms that prehistoric humans could have island‑hopped on purpose, using skill and strategy, effectively validating the long-hypothesized sea route as plausible.

From Science Labs to Global Headlines

The story has captured broad interest. Smithsonian and other outlets highlight that the team’s “efforts provide new insights into prehistoric mariners’ tools and techniques”. The University of Tokyo notes that the results were published in two Science Advances papers (one on the voyage, one on the modeling).

Scientific societies and educators are already using this adventure to engage the public: it’s a vivid, testable chapter of human history. Museums may update exhibits on Stone Age seafaring, and textbooks can now cite a hands-on proof that crossing the Kuroshio was within ancient reach.

How You Can Connect with This Story

For readers inspired by this feat, there are ways to explore further. The detailed studies are open-access in Science Advances, and the University of Tokyo press materials (including video clips) show the canoes’ making and voyage. History buffs might even visit Yonaguni Island (famous for its submerged rock formations) to imagine the distance involved.

Teachers and hobbyists can use this story as a case study in experimental archaeology. More generally, the project is a reminder: sometimes the best way to answer a historical question is to re-live it. Whether by reading the published papers or following outreach events, anyone can engage with the adventure of retracing ancient seafarers’ journeys.

Reflecting on Our Ancient Voyagers

In the end, the canoe experiment bridges 30,000 years. As Kaifu sums up: only the most seasoned, determined paddlers “could cross the sea with the strong current”. It underscores that early humans had advanced boatcraft and navigation far earlier than usually assumed. And as Helen Farr notes, seeing these “little human details” – the sweat, skill and strategy – is “a real, real joy” that static artifacts alone cannot provide.

Ultimately, by building and sailing a Stone Age canoe, scientists have not only tested a migration theory – they’ve brought ancient mariners’ experience vividly to life, reminding us of the courage and ingenuity of our distant ancestors.