A rock, discovered in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, has rattled America’s geologic history. Named the Watersmeet Gneiss, it’s the oldest rock yet confirmed in the United States.

Although Canadian rocks are still the oldest, this latest discovery changes what we know about the Earth’s ancient crust. With broad implications for fields such as planetary science and ancient biology, the Watersmeet discovery is not just an old stone, it’s a glimpse into Earth’s earlier years.

Now, scientists have a unique opportunity to unravel a previously unimaginable part of Earth’s geological past and finally find out what discoveries like this can mean for scientific advancement.

Redoing Textbooks—And Our World View

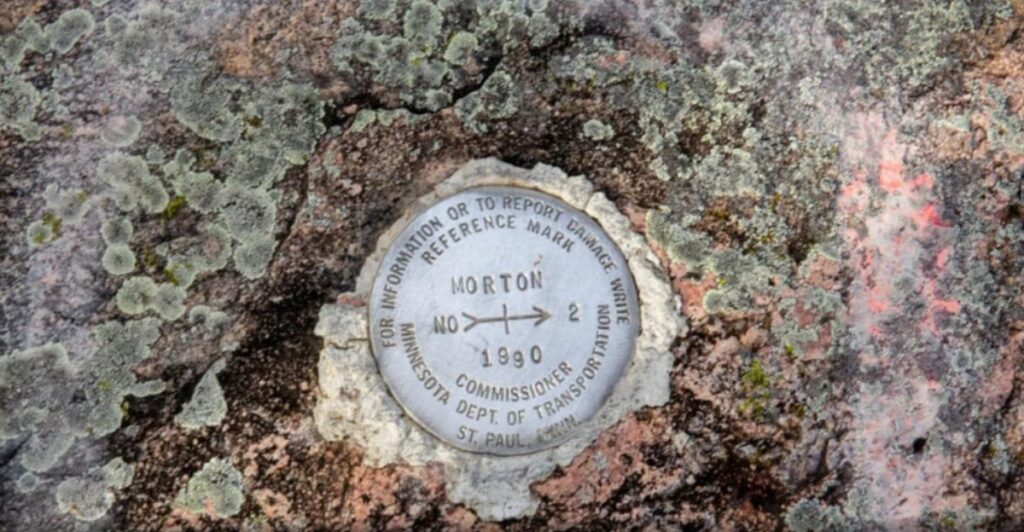

This discovery will force a rewrite of geology textbooks across North America. Most American students were taught that the oldest rocks can be discovered in Minnesota or Wyoming, but not anymore.

Michigan now holds that distinction, forcing teachers to rework not just regional maps but fundamental lessons about continental origins. Beyond schoolrooms, this discovery teaches us something entirely new about our geological history.

For a country that thinks of itself as new and young, a 3.6-billion-year-old rock is a reminder of Earth’s ancient roots. The Watersmeet Gneiss is not just a scientific find; it’s also a philosophical one as well.

Billionaire’s Paradise: Moon Rocks and Market Disruption

Given this, you might be surprised, and horrified, to learn that ancient rocks are now considered luxury collectibles. Billionaires buy Moon rocks and meteorites at auctions, raising the question: might Earth’s oldest rocks also become privately owned?

If the Watersmeet Gneiss happened to be on someone’s private property, would it have been saleable? Legally, yes. Ethically, absolutely not. Unfortunately, laws surrounding geological heritage are a bit behind the times, but it’s easy to imagine a startup marketing slivers of Archean rock as marvelous paperweights.

As space mining becomes a reality and exotic minerals seen as investment opportunities, America’s oldest rock is not just a scientific wonder—it’s a cultural icon waiting to happen.

The Politics of Rock Prospecting

Discovering ancient rocks isn’t necessarily academia—it can sometimes be geopolitical. Melting Arctic ice caps means that countries, such as Canada and Russia, find themselves battling to claim ownership of newly exposed crust.

Rare Earth metals, commonly embedded in ancient formations, are becoming strategic minerals. America’s Watersmeet Gneiss is commercially worthless, but it shows the increasing interest in billion-year-old rock areas.

Agencies such as the United States Geological Survey (USGS) now monitor these zones not just for science, but defense, mining, and even climate data. Therefore, rock formations once ignored and dismissed are now seen as valuable assets.

Canada Still Wins—By Billions

Canadians might yawn at America’s 3.6-billion-year-old discovery as their own Quebec Nuvvuagittuq greenstone belt is 4.03 to 4.28 billion years old, even older than Earth’s early oceans.

While the U.S. celebrates this legendary discovery, Canada already had older rocks beneath their feet since pre-multicellular times. But there’s more to it than mere age. America’s discovery is better preserved, offering a rare, unobstructed glimpse of early continental evolution.

In geology, it’s sometimes more important to have quality than quantity. Nevertheless, the amicable geological competition between the two countries shows that North America has access to unique ancient crust—something few other continents possess.

The Radiometric Time Machine

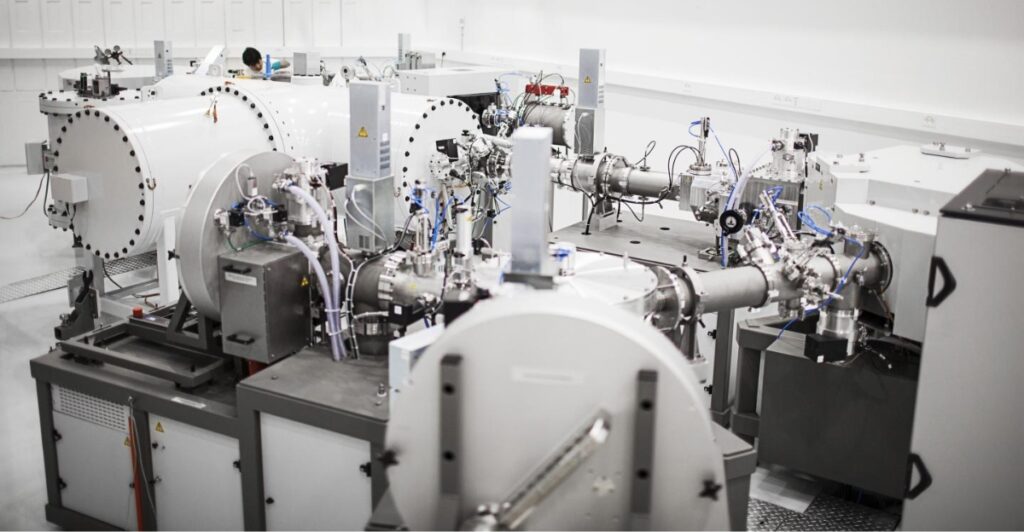

Analyzing rocks that are billions of years old demands atomic accuracy. Scientists employed neodymium and samarium isotopes to calculate the rock’s age. Since isotopes decay at a measurable rate, they essentially serve as a geological clock.

While uranium-lead dating is common practice, this discovery required a finer touch because of the rock’s metamorphic history. Therefore, measuring the isotopic ratio allowed scientists to make educated guesses of when the rock crystallized from molten material.

The method is so accurate that it can distinguish between events only a few million years apart; something rather important in understanding rock formation during Earth’s violent early years.

The Discovery That Changed American Geology

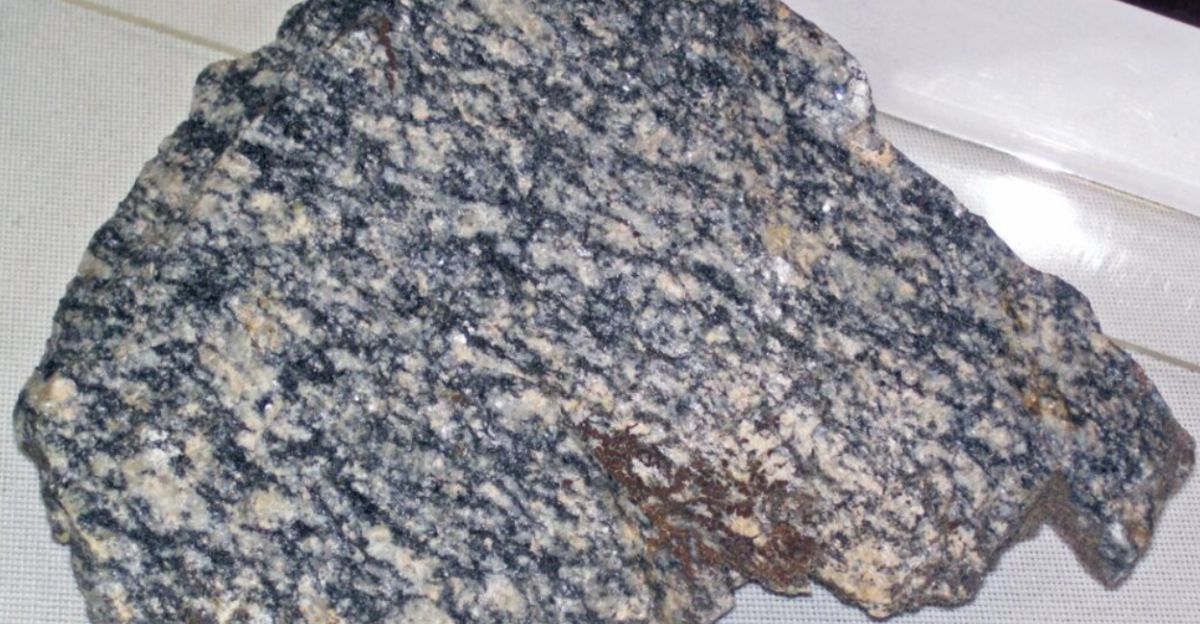

Found near Watersmeet, Michigan, the rock’s age was determined by University of Wisconsin-Madison geologists who used cutting-edge isotope analysis. Having been left undisturbed for centuries, radiometric dating revealed it to be of ancient origin, dating it to the Archean era in particular.

Previously, the oldest U.S. rocks were known to be roughly 3.4 billion years old and were mostly located in Minnesota and Wyoming. But the Watersmeet Gneiss predates them, changing our understanding of regional geologic chronologies completely.

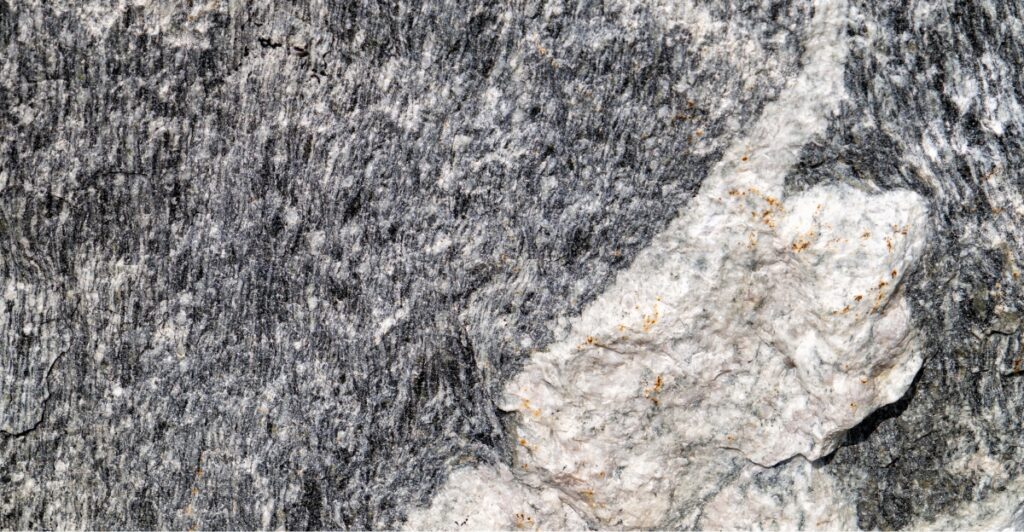

Scientists suspect that it could even have originated from Earth’s oldest continental crust, meaning that it could reshape our knowledge of when and how the American continent started to form.

What Ancient Rocks Teach About Early Earth

So why do we care about old rocks? Because they hold secrets to how Earth evolved and formed. The Watersmeet Gneiss tells scientists what early crust formations were like—the temperature, composition, and forces that influenced it.

In that period, Earth had no oxygen, and continents were just starting to form. With trace minerals and isotopic imprints, geologists learn how crust cooled, when oceans formed, and even the conditions under which life eventually evolved.

These rocks work like Earth’s early history black boxes. Without them, hypotheses about early tectonics, heat flow, and planetary origins would be mere theories or conjectural notions.

Early Crust and the Search for Extraterrestrial Life

This is where rocks meet life on other planets. Studying Earth’s earliest crust teaches astrobiologists about the potential for life elsewhere. If we know what conditions prevailed on early Earth, then we can mimic what to look for on Mars or Europa.

The Watersmeet Gneiss is a window onto prebiotic Earth—a time before life, when chemistry and biology were symbiotic. Its constituents, such as zircon and isotopic carbon signatures, may resemble those that scientists look for on other planets.

What’s Next? A Billion-Year Treasure Hunt

The Watersmeet Gneiss is likely not America’s last ancient rock discovery. With better equipment, geologists are targeting other Archean landscapes—Wyoming, Minnesota, and even the Appalachian Piedmont.

Any of them might be hiding more secrets. As machine learning and artificial intelligence enter the field, scientists can analyze maps, geochemical information, and satellite images faster than ever. The next 3.7-billion-year-old rock is perhaps buried under your neighbor’s backyard.

The more we explore, literally and metaphorically, the more we are reminded that the Earth has secrets buried beneath our feet that we cannot even imagine. It’s a billion-year treasure hunt, and the race is just beginning.