Something amazing has been brought to light just below the surface of a quiet Swiss village. While preparing land for new home developments at Kaiseraugst, archaeologists made a discovery believed to be a marvelously well-preserved Roman road—due to elegant porticoes, rarely-seen objects, and some very remarkably honest glimpses into the past.

The find has transformed a mundane dig into a historical revelation, unveiling the past of Augusta Raurica, a now-defunct wealthy Roman city. But what lies beneath the cobblestones? Why is this road so unique—and what secrets has it held in silence for close to two millennia?

A Quiet Town with a Grand Past

Kaiseraugst doesn’t exactly scream “Roman Empire,” but peel back a layer or two of soil, and a different story emerges.

This was where Augusta Raurica, a Roman colony from 44 BCE, stood. It’s the best-preserved Roman city north of the Alps, but even experienced archaeologists weren’t expecting such intact ruins in the center of a proposed housing development.

A Building Project Becomes a Time Capsule

The find wasn’t part of a large research expedition. It was a rescue dig—an effort to recover whatever historical remains were there before the digging started.

The site was close to a recognized Late Roman cemetery, so the team moved with care. They had no way of knowing they’d uncover a Roman road still lined with colonnades, revealing traces of an ancient city and life.

The Road That Time Remembered

At nearly 13 feet wide, this Roman road was no ordinary path. It was constructed to last, with repairs that were hundreds of years old. Flanked by drainage ditches and glorious porticoes on either side, it suggests infrastructure that considered aesthetics as much as it did functionality.

This was not simply a means of traveling from point A to point B—it was who they were. You can almost hear the scrape of sandals on its stone pavement.

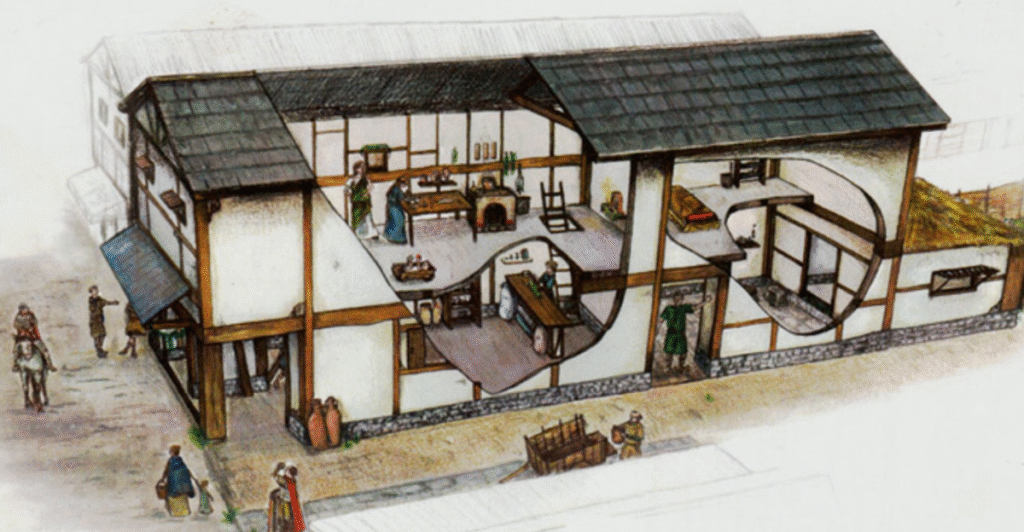

Houses That Ran Down the Street

Along the less prestigious sides of this street stood strip houses—long, thin houses typical of Roman provinces. Their floor plan allowed immediate access to the street, blurring public and private life in a manner that feels strangely contemporary.

Human beings lived, sold produce and food, and surely complained about the price of grain on this street. The ground floors of two of these buildings were open onto the street, offering us an architectural snapshot of everyday Roman existence.

Secrets Hidden in the Courtyards

Behind strip houses, archaeologists uncovered courtyards with stone-lined shafts. They may have been latrines or storerooms, but it was what lay alongside them that amazed archaeologists even more: miniature burials.

These were especially infant burials. They reflected Roman attitudes towards death, domestic ritual, and family. None of them were adorned with marble or imperial splendor.

When Grief Was Close to Home

High infant mortality was a grim fact of Roman life, and infant burials were intimate, muted farewells. The funerals here were not grand, but their location reveals something touching: families didn’t want to be too far removed from their children, even after their death.

It’s a reminder that beneath the authority of the empire were very human, emotional lives.

Extraordinary Context, Ordinary Finds

Pottery shards, coins, and fragments of glass littered the ground. These objects were nothing special, but when considered in that context—along the same street people walked daily—they come alive.

They speak to routine, habit, and familiarity. Coins signify trade, glass, craftsmanship and pottery, food.

Enter the Panther

And then the surprise. Brought up out of the ground, a small bronze panther appeared—in beautifully made and symbolic detail. It could have been a votive object or domestic idol, giving us a glimpse into religious life in the provinces.

Panthers were usually associated with Bacchus, the god of Roman wine and drunkenness. Either way, this small panther statue was not just for show. It was deliberately made and cherished for centuries.

Small Treasures, Big Meanings

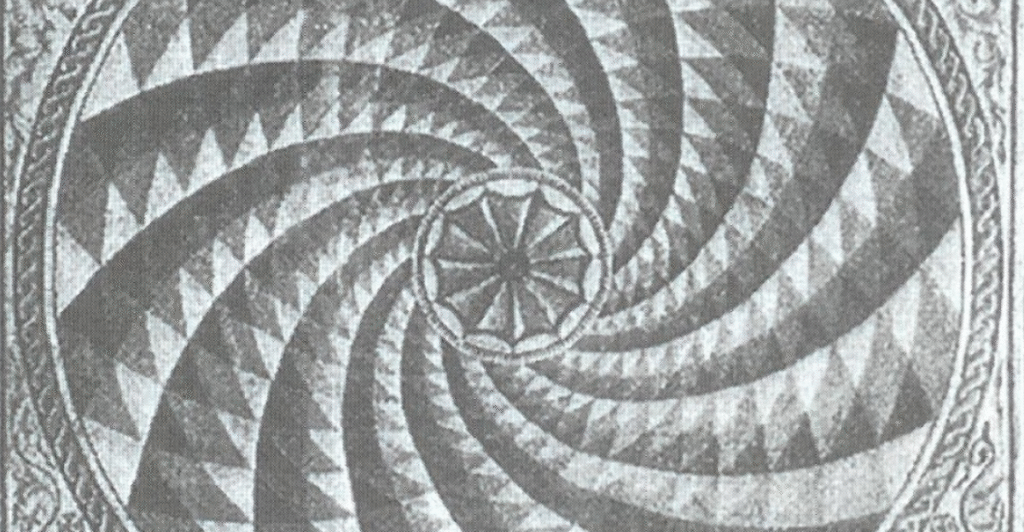

More treasured discoveries followed: a votive dish made of volcanic tuff, and a glass mosaic spindle whorl. The whorl suggests work with textiles—a prosaic activity, maybe, but an art form.

These pieces had a purpose and sometimes spiritual significance. It’s in these objects that we see the unpretentious richness of Roman domestic life.

Digitally Dug, Digitally Saved

The Aargau Cantonal Archaeology Department digitally recorded the excavation for the first time. Everything was recorded directly into a database in real time: all artifacts, trenches, and layers.

This meant ultra-high-precision preservation of context, with less opportunity for human error and more efficiency.

A Blueprint of Roman Life

With this cutting-edge technology, archaeologists today have a very detailed picture of this Roman community. The street, porticoes, homes, courtyards—all as pieces in a historical jigsaw puzzle.

And rather than hypothesizing what was where, now they can document evidence to support their theories, plot relationships, and map patterns. They can reconstruct the ancient world.

A City Reimagined

With every stone turned, Augusta Raurica is more than a just a spot on a map. It was a place where romans lived, worked, prayed, and wept.

This discovery in the lower town fills in the blanks of our understanding of its urban layout and social structure. It doesn’t simply establish the city’s importance—it gives it depth. A Roman road, after all, was never only just stone—it was a link that held layers of meaning.

Echoes from the Earth

So what can we learn from this? Perhaps history lies in plain sight, just waiting for the perfect moment—or modern technology—to rediscover it.

Perhaps human existence, with its rituals and routines, hasn’t really changed that much. And perhaps the greatest stories are not always within ancient pages but in the earth itself, in quiet moments, and in the gentle curve of a forgotten miniature bronze statue.