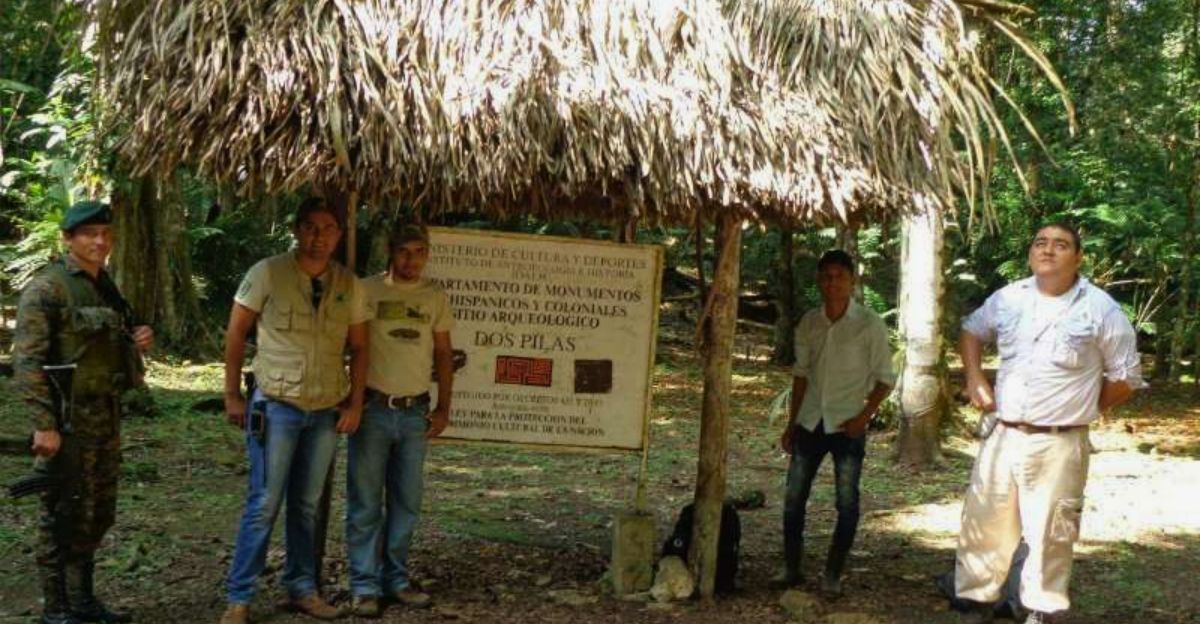

Researchers have uncovered one of the most chilling examples of ancient Maya ritual practices deep beneath Guatemala’s jungle. According to California State University bioarchaeologist Michele Bleuze, the cave known as Cueva de Sangre contains over 100 fragmented human remains showing clear signs of violent trauma. The cave, part of a network beneath the ancient Maya site of Dos Pilas, was first discovered in the 1990s but only recently analyzed in detail. What they found has completely changed how scientists understand Maya religious ceremonies and the lengths communities would go to appease their gods.

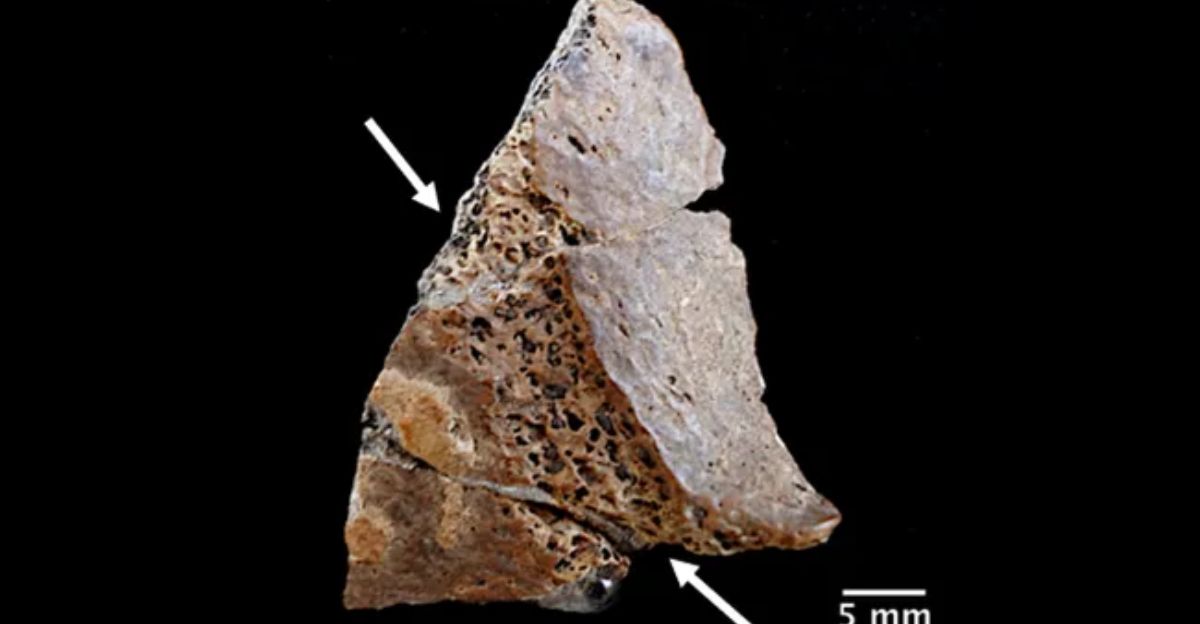

Evidence Points to Systematic Violence

The bones tell a story that gets more disturbing with each piece of evidence researchers uncover. As reported by Live Science, the remains show perimortem trauma consistent with ritual dismemberment using obsidian blades. Ellen Fricano, a forensic anthropologist at Western University of Health Sciences, found cut marks on skull fragments that match tools like hatchets, made around the time of death. Red ochre and obsidian weapons recovered alongside the bones provide additional evidence of ceremonial activity. The arrangement suggests the bones were deliberately placed rather than discarded after death.

Sacred Underground World of the Maya

Maya civilization has long been associated with complex ritual practices, but caves held special significance in their cosmology. According to Maya archaeology experts, caves were viewed as entrances to the underworld, sacred spaces where the living could communicate with deities and ancestors. The Dos Pilas cave system, discovered during surveys in the 1990s, contains more than a dozen interconnected chambers dating to between 400 BC and 250 AD. During this period, Maya communities used caves for everything from water storage to religious ceremonies, making them focal points of spiritual life across Mesoamerica.

Seasonal Access Creates Mystery

What makes Cueva de Sangre particularly intriguing is its unique accessibility pattern. According to archaeological reports, the cave can only be entered during Guatemala’s dry season from March to May, when water levels drop enough to expose the entrance passage. The cave remains completely flooded for the remaining months, sealing off its contents from the outside world. This seasonal flooding may have been intentional, as Maya communities often associated water cycles with agricultural fertility and divine favor. The timing aligns perfectly with modern Maya ceremonies for rain gods like Chaac.

Bodies Become Ritual Offerings

Here’s what shocked researchers most about their findings. According to Michele Bleuze’s presentation at the Society for American Archaeology meeting in April 2025, these weren’t traditional burials but evidence of systematic ritual dismemberment. “The emerging pattern that we’re seeing is that there are body parts and not bodies,” Bleuze explained to Live Science. Analysis revealed that victims were deliberately dismembered, with specific body parts selected for ritual purposes. The bones were arranged in patterns consistent with offerings to Chaac, the Maya rain god, during drought periods when communities desperately needed divine intervention for crop survival.

Guatemala Protects Archaeological Heritage

The discovery has sparked intense interest among Guatemala’s archaeological authorities, who oversee the country’s extensive Maya heritage sites. According to the Cultural and Natural Heritage Bureau, the Dos Pilas site falls under strict archaeological protection laws established in 1997. While the cave remains naturally restricted by seasonal flooding, there’s no evidence of formal sealing by authorities following the recent analysis. The site continues to attract researchers and tourists interested in Guatemala’s pre-Columbian history, though access remains limited to the dry season months when conditions allow safe entry.

Scientists Grapple with Disturbing Evidence

The researchers involved describe their work as both fascinating and emotionally challenging. According to interviews with the research team, working with evidence of such systematic violence required careful preparation. Michele Bleuze noted that examining cut marks on children’s bones was particularly difficult, even for experienced bioarchaeologists. Ellen Fricano emphasized the importance of respecting the remains while extracting maximum scientific value from the evidence. Team members say the work has deepened their understanding of Maya ritual complexity while raising new questions about ancient social dynamics.

International Collaboration Advances Research

The research involved scholars from multiple institutions working under Guatemala’s archaeological cooperation agreements. According to Cal State LA reports, the project brought together bioarchaeologists, forensic anthropologists, and Maya specialists to analyze the complex evidence. International academic protocols require careful documentation and sharing of findings through peer-reviewed publications and conference presentations. The collaboration demonstrates how modern archaeological research transcends national boundaries while respecting host countries’ cultural heritage laws and community interests throughout the investigation.

Similar Discoveries Across Maya World

Similar evidence of ritual human sacrifice has emerged across the broader Maya world, suggesting these practices were more widespread than previously understood. According to research from sites like Chichen Itza and other ceremonial centers, Maya communities practiced various forms of human sacrifice for different religious purposes. Recent DNA analysis of child sacrifices at Chichen Itza revealed connections to creation mythology and rain ceremonies. The practice appears to have been closely tied to agricultural cycles, with sacrifices timed to coincide with crucial farming periods when divine favor was most desperately needed.

Rain God Demanded Ultimate Sacrifice

Archaeological evidence suggests these sacrifices were explicitly intended to appease Chaac, the Maya rain god, during critical agricultural periods. According to studies of Maya religious practices reported by EBSCO Research, Chaac was believed to control rainfall, which is essential for crop survival. The timing of cave ceremonies during the dry season, combined with water-related symbolism and seasonal flooding patterns, points to desperate attempts to secure divine intervention. This reveals that what initially appeared to be random violence was systematic religious practice tied to community survival during drought periods that threatened their agricultural foundation.

Modern Maya Maintain Complex Relationship

Contemporary Maya communities have complex relationships with these archaeological discoveries. According to ethnographic studies, modern Maya still perform ceremonies requesting rain from Chaac without human sacrifice. Some community leaders express concern about sensationalized coverage of ancient practices, worried it reinforces negative stereotypes about indigenous cultures. Others appreciate the scientific attention that helps preserve and understand their ancestors’ beliefs. The discoveries raise questions about how archaeological findings should be presented to respect scientific accuracy and cultural sensitivity for living descendants.

Preservation Challenges in Remote Location

Managing and preserving the Cueva de Sangre site presents unique challenges for Guatemalan authorities. According to archaeological site management reports, the seasonal flooding that once protected the cave now complicates preservation efforts. Climate change threatens to alter water patterns, potentially affecting the site’s natural protection mechanisms. Authorities must balance scientific access with preservation needs while ensuring local communities benefit from increased research interest. The site’s remote location and limited access window make regular monitoring and maintenance particularly difficult for heritage protection agencies.

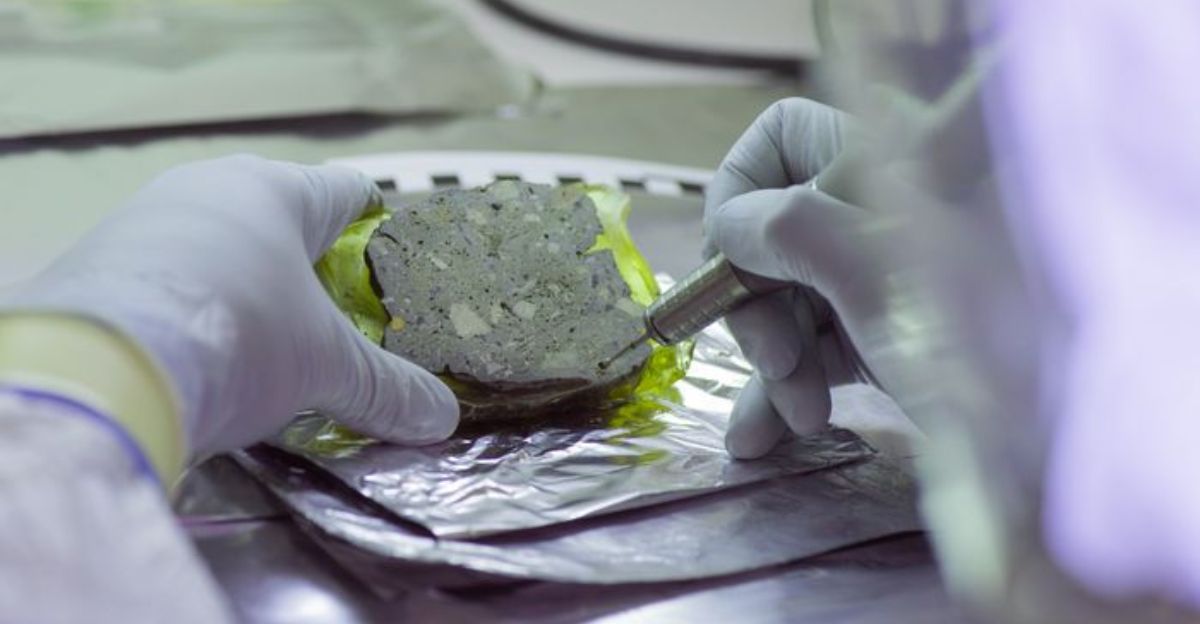

Future Research Plans Expand Understanding

Scientists plan to conduct extensive additional analyses of human remains and artifacts. According to research proposals, teams want to extract ancient DNA from bone samples to learn more about the victims’ origins and relationships. Stable isotope analysis could reveal information about their diets and migration patterns before death. Advanced dating techniques may narrow down the timeline of ritual activities. Researchers also hope to explore other caves in the Dos Pilas system to understand the full scope of ritual activities that took place throughout the underground network.

Scientific Community Debates Interpretations

Not all experts fully agree with the interpretation of the evidence regarding ritual sacrifice. According to some bioarchaeologists, additional evidence would strengthen conclusions about intentional ceremonial killing versus other explanations for the bone patterns and trauma. Critics note that violent death doesn’t automatically indicate ritual sacrifice, and more context is needed to prove ceremonial intent definitively. However, the combination of evidence, including bone arrangement, associated artifacts, cave location, and seasonal timing, creates a compelling case for the ritual interpretation that most specialists in Maya archaeology now accept.

Ancient Mysteries Continue to Unfold

As researchers continue analyzing the Blood Cave evidence, each discovery adds new chapters to our understanding of Maya civilization’s complexity. The systematic nature of these ancient practices reveals sophisticated religious beliefs that governed life and death decisions in Maya communities. While disturbing by modern standards, these rituals represent desperate attempts by ancient peoples to ensure their communities’ survival through divine intervention during times of crisis. What other secrets remain hidden in Guatemala’s countless caves, waiting for the right combination of technology, timing, and scientific curiosity to reveal the full story of Maya spiritual practices?