Far down beneath the rugged wilderness of Idaho’s northwestern corner, archaeologists have uncovered secrets that will revolutionize all we thought we knew about the first human settlement in North America.

Our schoolbooks have long been teaching a very specific tale: ancient human beings trekked over an icy land bridge, following animal herds migrating to a new land. But what if the real story is stranger, older, and far more complex?

In a peaceful river valley, buried for thousands of years, new evidence of our past has emerged, creating controversy, proposing an epic migration that undermines traditional understanding and throwing all we know into question. The very earth seems to whisper that our history is not what we believed.

Why Idaho’s Find Is Heard Globally

The impact of this great discovery found in Cooper’s Ferry, Idaho, echoes far beyond local interest. If proven true, these ancient remains could rewrite the world’s history of man’s migration, completely changing our idea of how people settled on the continents.

Scientists in Tokyo and Toronto are on tenterhooks as the evidence throws everything into question. When exactly did man truly master the Americas? Was it through canoeing down uncharted coasts, or trekking across icy steppes?

The site has drawn media attention, scholarly fascination, and even viral TikTok breakdowns of every proposed theory and found artifact.

The Cooper’s Ferry site

Before the world knew what was hidden beneath Idaho’s soil, the Cooper’s Ferry site was a remote Salmon River bend, known to the Nez Perce Tribe as the ancient village of Nipéhe.

It wasn’t until the 1990s when archaeologist Loren Davis, who was working for the Bureau of Land Management at the time, started to seriously explore the site. Years later, Davis, now a professor at Oregon State University, returned with a team of researchers and students for a decade-long excavation from 2009 to 2018.

Their painstaking, slow work—digging, sifting, and analyzing—would eventually set off a chain of events that may improve our understanding of North America’s earliest residents.

The Emotional Hype of a New Origin Story

For many, the idea that humans settled North America thousands of years earlier than believed is both thrilling and unsettling. Now, archaeologists grapple with the thrill of discovery and the burden of refuting cherished ideals.

Meanwhile, Native American communities, especially the Nez Perce, feel a deep sense of connection and acknowledgement as their tales, which spoke of ancient life in Nipéhe, are now being confirmed by science.

Now, Reddit, YouTube and other online forums are ablaze with expectant and skeptic posts in equal measure, as people debate what it is to be a citizen of a country whose past just got much older and more mysterious.

What We Thought We Knew

For most of the 20th century, the story of America’s first settlers was dominated by the “Clovis First” theory. It speculated that the continent’s earliest residents arrived about 13,000 years ago having crossed the Bering Land Bridge from Siberia and moving south through an ice-free corridor as the glaciers retreated.

This belief was based on the discovery of characteristic fluted stone points at New Mexico’s Clovis site and duplicated in similar finds across North America. But in the 1970s and 1980s, archaeologists began excavating sites that revealed artifacts and butchered animal remains that appeared still older.

Why the Old Theories Are Under Attack

For nearly a century, the “Clovis First” hypothesis had unchallenged dominance. But the more scientists dug—literally and figuratively—the more they uncovered artifacts that didn’t quite fit the timeline.

Places like Monte Verde in Chile hinted at previous migrations, but those were dismissed by skeptics as anomalies, error or misinterpretations. More conflicts grew as more evidence emerged, which pointed to migration routes that circumnavigated the alleged ice-free corridor.

Now, the Cooper’s Ferry site, with its meticulously dated stratigraphy, is now the epicenter of this ongoing scientific back-and-forth debate.

Idaho’s Ancient Settlement Revealed

The true surprise came when archaeological excavations at Cooper’s Ferry in Idaho uncovered stone tools, fireplaces, and animal remains—radiocarbon dated to as much as 16,560 years ago.

That’s more than a thousand years before the opening of the Bering Land Bridge ice-free corridor, suggesting that the first Americans didn’t arrive on foot but maybe by boat down the Pacific coast. Overall, the site yielded 189 artifacts, 27 of which were stone tools and horse remains encircled by tools.

This evidence indicates that the earliest Americans were skilled hunters and butchers. Ultimately, the site and its artifacts and specimens necessitates a complete reconsideration of when—and how—humans first occupied North America.

What This Means for Your Backyard

If Idaho’s river valleys harbored humans 16,000 years ago, what other hiding places might North America have? The discovery inspires archaeologists to revisit ancient sites and dig more deeply, literally and figuratively, for potentially overlooked evidence.

It has also proven to intrigue and fascinate locals—could your town also hold secrets of our collective past? Universities and museums nationwide are reevaluating collections, and amateur historians and Indigenous populations have begun to explore the stories passed down through generations.

The ripple effect is undeniable: our ancient history feels closer, more immediate, and more unfinished than ever before.

Scientists, Tribes, and the Land

Behind the headlines are the scientists who spent years working in the mud, Niimíipuu tribal members whose relatives named the site Nipéhe, and skeptics who doubt everything.

The collaboration between archaeologists and the Nez Perce Tribe unites technical rigor and cultural depth, marrying radiocarbon dating with oral history. The emotional investment is considerable: for some, it’s validation; for others, it’s a challenge to strongly held beliefs.

While arguments are passionate, they remain civil, with both sides agreeing that this is not merely about bones and rocks, but about our shared identity and belonging.

A Broader Shift: Rethinking the Human Journey

Idaho’s ancient settlement is not an isolated anomaly—it’s part of a new pattern that’s redefining our picture of human migration. Sites in Oregon, Texas, and even Pennsylvania are being excavated once again for traces of past occupation.

The Pacific coastal migration hypothesis gains credence, suggesting that ancient humans were not only hunters but also skilled sailors. This paints a picture of communities that were not simply land-based migrants.

This broader narrative provides new information about the settlement of the Americas, and tells a story of innovation, adaptability, and resilience. It compels us to view early Americans not as passive herd followers, but as pioneering adventurers shaping new worlds.

What’s Next? Questions for a New Era

With every new find, the story grows richer—and more complicated. Will additional excavations confirm the timeline suggested in Idaho, or will new discoveries push the date even further back?

How will this reshape education, museum exhibitions, and even tourism in what were once considered historical backwaters? The question is far from settled, and the stakes are huge: our understanding of the first Americans keeps evolving.

As science becomes more advanced and Indigenous viewpoints are increasing considered as more than mere legends and myths, new findings will likely bring with them even more surprise. One thing is for sure, however: North America’s true story is yet to be written.

The Lasting Impact: Why This Matters Now

The Idaho Cooper’s Ferry site evidence is not just a milestone in science, it’s a cultural breakthrough, a reminder that the past is not history alone, but something that is alive, contested, and very much relevant.

It challenges us to question our assumptions, embrace complexity, and hold both scientific evidence and Indigenous knowledge with higher esteem. Amidst the furious arguments wreaking havoc online and the scholarly journals, one thing is absolutely certain: the initial human settlement of North America is not a relic of the past.

In fact, the discovery speaks more to who we are, where we come from, and how we choose to remember our past. In the end, Idaho’s earth has given us not just answers, but the call to keep asking questions.

Clovis: The Once-Untouchable Benchmark

For decades, the gold standard has been New Mexico’s Clovis site. So named because of the distinctive spear points that were discovered there during the 1930s, it was the definitive proof of the earliest human presence in North America.

Found to be about 13,000 years old, the fluted, pointed tools were undisputed. But now that older sites are being discovered in places like Cooper’s Ferry, archaeologists are being forced to ask if Clovis was an alpha point—or just a chapter.

Clovis vs. Cooper’s Ferry: A Switch in Timeline

The most significant difference between Cooper’s Ferry and Clovis isn’t where it was located—it’s when. Cooper’s Ferry artifacts date to more than 16,500 years ago, more than 3,000 years before Clovis.

The Clovis folk, who stalked mammoths, wouldn’t have the same land-based way of living in river bottoms and along shorelines.

This shift from desert to riverine and coastal living gives us a more nuanced and complete image of how early humans lived through the diverse landscape of North America.

Other Tools, Other People?

Clovis tools are symmetrical, wide, and for killing large game. Cooper’s Ferry tools, on the other hand, narrower, cruder, and more diverse.

And this brings up a very big question: were they produced by the same individuals, changing over time—Or were they made by entirely different cultures?

The theory that various human populations migrated into North America separately, perhaps by different routes and methods, is finally gaining traction in the scientific community.

An Early Human Highway?

The coastal migration hypothesis—migrating by boat up and down the Pacific Coast—is gaining acceptance with places such as Cooper’s Ferry.

In contrast to Clovis, which suggests a land-based migration, Cooper’s Ferry accommodates a sea route, possibly even using dugout canoes.

That route bypasses the cold interior of North America for a more direct route to rivers and sources of food—and perhaps explaining how people arrived there sooner than realized.

Discovering the Surprise in a Tent Classroom

The Cooper’s Ferry archaeological site is not only for researchers; it’s a living classroom too. Oregon State University conducts summer field schools, where students and volunteers excavate with experts.

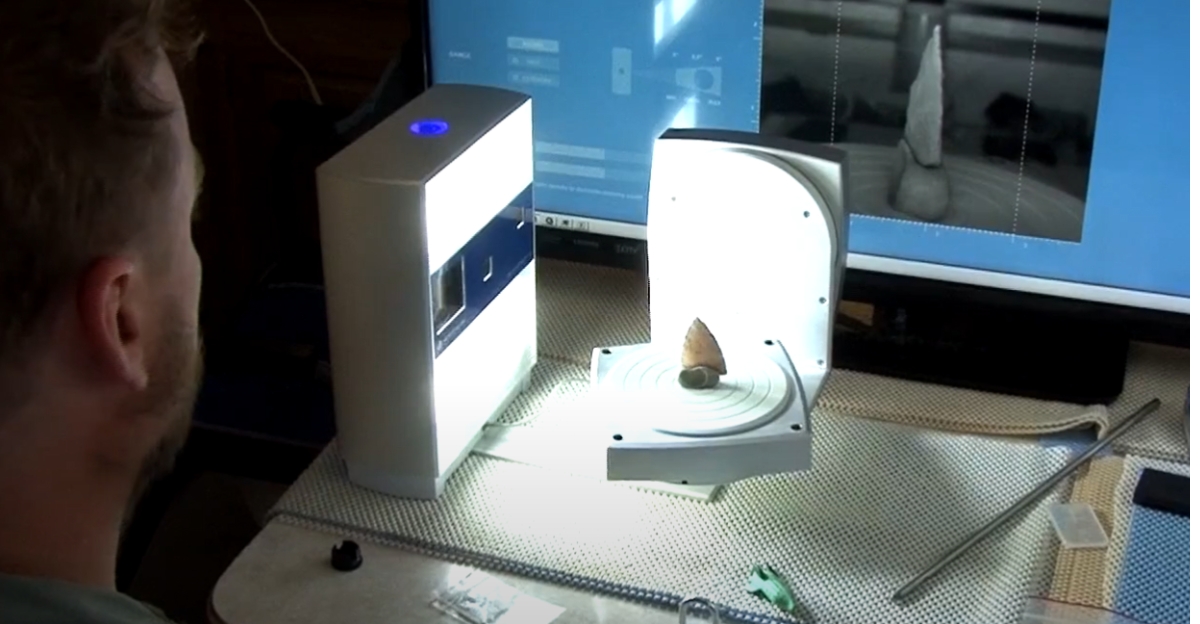

They’re taught to interpret soil layers, deal with delicate artifacts with care, and interpret ancient remains.

For some, it’s a once-in-a-lifetime experience: getting in the mud and literally unearthing human history while rewriting what we previously assumed to know about our forefathers.

Community Meets Discovery

What’s interesting about the Cooper’s Ferry site is how it brings education and public outreach together. Local school students visit the site on field trips, and some even get a few minutes at supervised small digs.

The goal? To encourage the next generation of historians and archaeologists—while getting kids to understand that the part of town they live in once hummed with prehistoric activity. The site is at once a scientific treasure and a classroom for culture.

The Contributions of the Nez Perce Youth

The Nez Perce Tribe is not sitting on the sidelines watching—instead, they are striving diligently to keep Nipéhe’s history alive and educating youth about their heritage.

Tribal school-sponsored youth programs provide hands-on training in archaeology, language survival, and oral history documentation.

These programs do more than teach skills—they build a sense of pride. Young Niimíipuu are becoming the keepers of their people’s very ancient history, reaffirming cultural identity in the process.

Preserving the Land, Preserving the Past

Archaeologists and members of the Nez Perce nation have gone out of their way to balance exploration and conservation.

Excavation at Cooper’s Ferry is strictly regulated to avoid disturbing sacred grounds and make minimal impact. Soil is carefully removed in layers for sampling, and each artifact is carefully documented.

This joint effort demonstrates respect for both scientific inquiry and spiritual heritage—a model of how archaeology can be a more respectful, inclusive science.

Clovis Still Matters—But Differently Now

Despite the focus placed on Cooper’s Ferry, the Clovis site remains very valuable. It shows a distinct wave of migration, possibly from elsewhere. Instead of being the first Americans, the Clovis residents may have been members of various groups.

Discovering where these waves intersected or diverged might be the next archaeological enigma. That way, Clovis remains relevant—but as an extension.

A Call to Keep Digging—Everywhere

If Cooper’s Ferry and Clovis taught us one thing, it’s this: history still conceals countless mysteries. Oregon, Florida, and even Canada hold sites now in the process of being excavated further, particularly around coasts and riverbeds.

With advances in dating technology and partnerships with Indigenous peoples, even more sites like Cooper’s Ferry can be expected to turn up. Our understanding of the past still isn’t complete. We just have to keep digging—and listening.