A teenage schoolboy jogging along Sanday’s windswept beach in Scotland’s Orkney Islands suddenly spotted heavy oak beams thrust from winter-scoured sand in February 2024.

The unexpected find excited residents because timber that size rarely appears intact, even on this shipwreck-ridden coast. The community got involved as farmers soon fetched tractors, determined to save the fragile relics before fierce Atlantic tides reclaimed them later that afternoon.

Shipwreck Island

Sanday’s shoreline is notorious for shipwrecks. In the last 600 years, historians count roughly 270 recorded wrecks around its 20-square-mile perimeter. The island sits where the North Sea and Atlantic collide, producing currents that mariners once feared more than pirates.

According to Orkney Islands Council archives, cargo ships, whalers, and warships lie beneath these waves, earning Sanday the sobering nickname “Scotland’s cradle of shipwrecks.”

Race Against Time

Climate-driven storms revealed timber that’s survived countless years, but they also threatened to destroy it. Researchers from Historic Environment Scotland warned that air and sun can collapse centuries-old wood in days.

To save the twelve tons of waterlogged oak, volunteers dragged it inland with borrowed trailers, according to Wessex Archaeology. Their improvised operation bought critical time until specialists arrived with spray systems and protective sheeting equipment.

Scientific Sleuthing

Scientists sampled tiny tree-ring plugs from planks to uncover the vessel’s identity. Dendrochronology matched growth patterns to oak felled in southern England during the 1740s and 1750s.

Shipbuilding records were cross-checked, narrowing candidates to a handful. Ben Saunders of Wessex Archaeology said eliminating Northern European timbers left “two or three likely names,” setting the stage for a remarkable historical confirmation soon. However, no one would know the impressive history behind the piece of the wreck.

Revolution Revealed

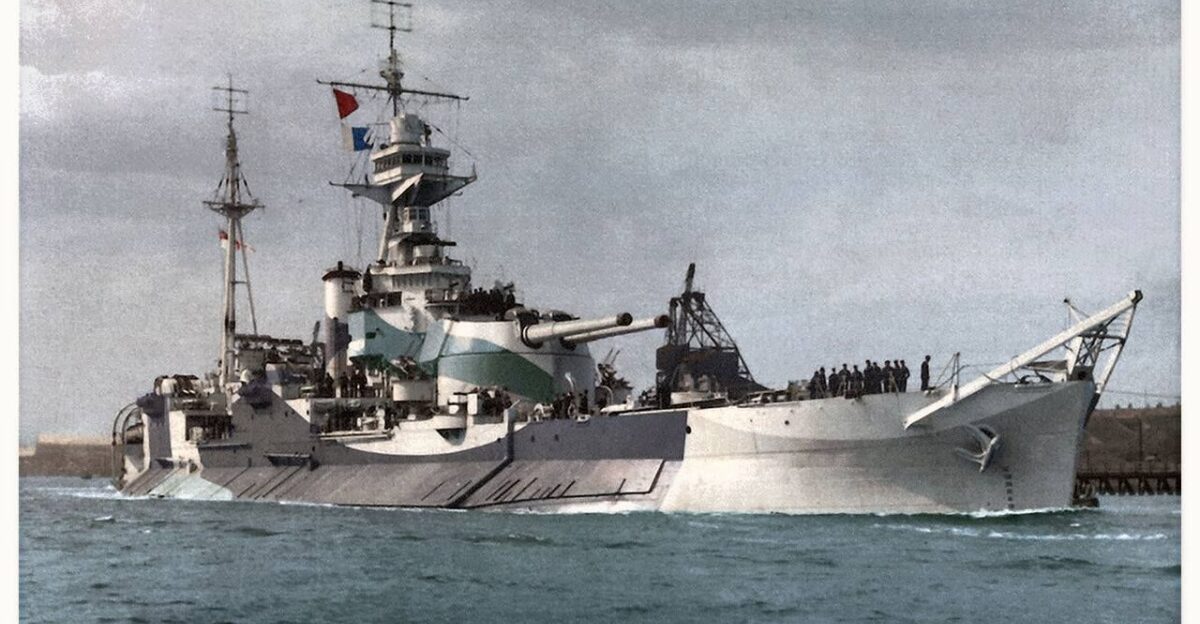

Archival logs led to the identification of the vessel as the wreck of HMS Hind, a 24-gun Royal Navy frigate built in 1749. Maritime records show she intercepted at least four American privateers in 1780-1781, guarding convoys during the Revolutionary War.

After the Revolutionary War ended, the HSM Hind was destined for decommission in 1784. The Hind was sold to London whaling interests under the name Earl of Chatham, and continued earning profits in Arctic seas before wrecking off Sanday in 1788.

Community Spark

The boy has remained anonymous to protect his privacy. His discovery galvanized Sanday’s 500 residents. Community researcher Sylvia Thorne recalled, “It was a great experience—everyone came together.” Volunteers catalogued planks, compared nail patterns, and emailed maritime archives worldwide.

According to BBC News, the wreck gained the interest of many community members: schoolchildren logged shore measurements for science class. At the same time, retirees monitored humidity inside temporary storage tents, proving that small islands can contribute significant expertise to international archaeological projects and success.

Heritage Heroes

Custodian Ruth Peace coordinated preservation efforts at the Sanday Heritage Centre. Volunteers sprayed freshwater hourly, stopping salt crystals from splitting oak fibers.

Orkney Islands Council videos show homemade rigs of lawn sprinklers suspended above timber stacks. Ben Saunders praised the dedication, noting that many heritage sites lack such grassroots energy. Their vigilance kept the wreck intact until a permanent conservation tank became available.

Whaling Boom

Earl of Chatham’s whaling refit highlights booming Arctic ventures of the 1780s. Gresham College research counts over 100 London ships annually, lured by government bounties of 40 shillings per ton of oil. Strengthened hulls let converted warships press deeper into ice.

Shipping lists record the vessel taking nineteen Greenland whales across four profitable seasons, supplying Britain with lamps, soap, and machinery grease.

Convoy Guard

The HSM Hind played a pivotal role during the American Revolution. At this time, Britain relied on frigates like Hind to protect commerce.

According to the Washington Post, naval dispatches credit her with seizing privateers Charming Sally and Julius Caesar, limiting colonial raiders’ reach.

Double Duty

The vessel’s dual career illustrates 18th-century thrift. Naval architecture built for cannon fire also resisted crushing pack ice, making decommissioned warships valuable Arctic assets.

Earl of Chatham’s story mirrors dozens of frigates sold into commerce once peace reduced defense budgets. Economists say repurposing saved owners months of construction and thousands of pounds, accelerating Britain’s industrial appetite for whale oil and related products.

Tank Lifeline

In September 2024, the National Heritage Memorial Fund awarded £79,658 to build a stainless-steel freshwater tank safeguarding the wreck. Culture team manager Nick Hewitt thanked the fund for responding “so quickly” to avert decay.

Fabricated in Aberdeen by Waterfront Stainless Steel, the tank allows controlled desalination, buying conservators years. Without this intervention, oak planks could have fragmented into unusable shards of evidence.

Shared Science

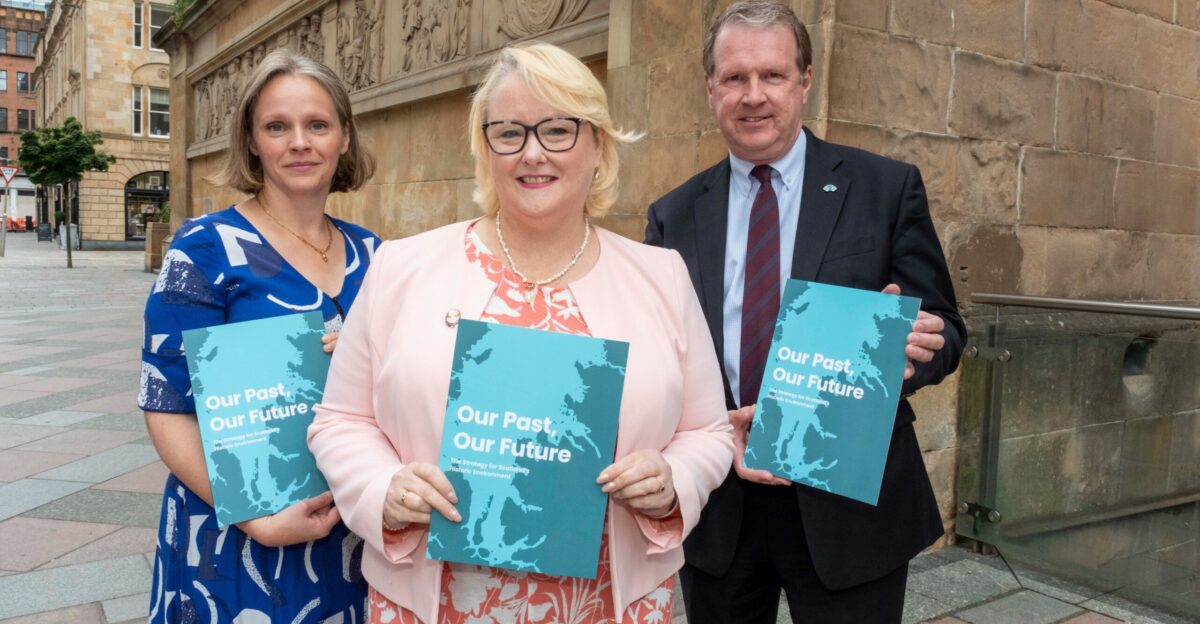

Historic Environment Scotland, Wessex Archaeology, and Dendrochronicle formed an unusual alliance with Sanday volunteers. Specialists provided lab equipment; locals offered vigilance and regional knowledge.

Alison Turnbull of Historic Environment Scotland says empowering communities “lets them tell the story of their historic environment.” The partnership demonstrated how citizen scientists, when guided, can unlock discoveries normally requiring large budgets and university teams alone.

Slow Preservation

Today, the timbers rest in treated fresh water inside Sanday Heritage Centre, starting a decade-long conservation program. Specialists will gradually replace water with polyethylene glycol, preserving cell walls before freeze-drying.

Visitors already view the process through observation windows, learning why removal is impossible yet protection is essential. The project positions Sanday as an unexpected hub for global maritime research on the Revolutionary War.

Top-Five Find

The wreck ranked among Scotland’s five most impressive archaeological finds of 2024, according to Dig It! Scotland. Maritime historian Tom Muir believes its dual Navy-whaler identity offers rare insights into late-eighteenth-century ship reuse.

Researchers caution that funding gaps could delay the analysis of fittings still buried offshore. Continued community engagement will be vital to maintaining momentum and securing specialist resources and attention.

Future Finds

Rising seas and harsher storms increasingly uncover hidden wrecks along Britain’s coasts. Experts warn that each revelation triggers a race against decay and limited budgets. Sanday’s success poses a provocative question: Will future communities muster similar commitment when the next Revolutionary War relic surfaces?

The answer may decide whether climate change erases maritime heritage or unexpectedly expands historical understanding for humanity.