There are many hidden secrets buried beneath sand, stone, and water across the earth. In a recent surprise, archaeologists are uncovering remnants of technological marvels from a similar era, dugout canoes crafted by Indigenous peoples as many as 4,500 years ago.

Recent underwater discoveries have identified dozens of these ancient vessels, revealing a rich legacy of travel, trade, and adaptation along inland waterways. Where did these canoes come from, and what exactly were they used for?

The First Find

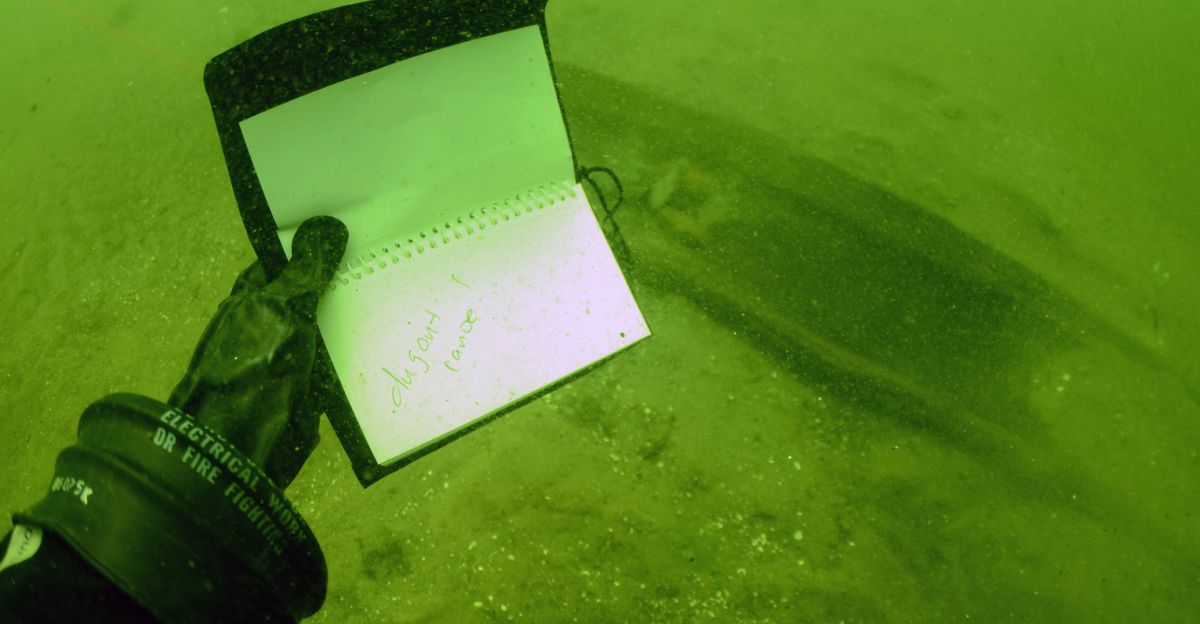

In 2021, maritime archaeologist Tamara Thomsen was scuba diving in Wisconsin’s Lake Mendota when she spotted a piece of wood sticking out of the sand. She set in motion a sequence of discoveries that would reshape the region’s archaeological map. The first two finds, one dating back 1,200 years and another a staggering 3,000 years, quickly attracted wider scientific attention.

These efforts revealed multiple canoes, some possibly 4,500 years old, hidden along a former shoreline now submerged beneath the waters. “What I did not understand was the breadth of the discovery,” said Tamara Thomsen.

Lake Mendota: Home of the Finds

Lake Mendota, known as Tee Waksihominak in the Ho-Chunk language, has quietly preserved these ancient secrets in its silty, cold depths for millennia.

Archaeologists believe the cache accumulated along an ancient shoreline, where Indigenous communities may have intentionally stored their canoes underwater during winter to protect them from freezing and warping.

How Many Canoes?

As of May 2025, archaeologists have documented as many as 11 dugout canoes concentrated along roughly 800 feet of what was once an ancient shoreline. This is the largest single grouping of prehistoric canoes ever discovered in the Great Lakes region, with the oldest dating back 4,500 years and the youngest about 800 years old.

Some canoes are largely intact, while others survive only as wood fragments, and ongoing scientific analysis may reveal precise counts as research continues.

As Ancient as the Egyptian Pyramids

Radiocarbon dating has established that the oldest canoe in the Mendota cache is approximately 4,500 years old, dating back to around 2,500 B.C.E., nearly the same era when the Great Pyramid of Giza was constructed in ancient Egypt.

“The canoes are telling the story of the people who have been here for a very long time, regardless of what they call themselves,” said State Archaeologist Amy Rosebrough.

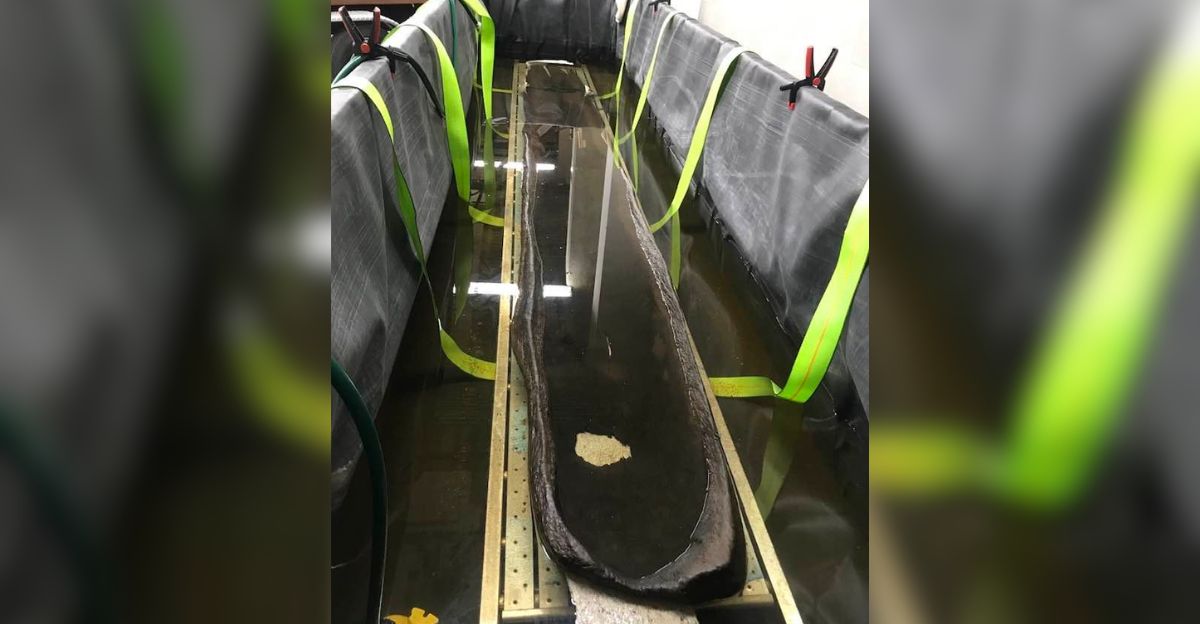

Preservation and Fragility of the Canoes

For centuries, the cool, low-oxygen environment at the lake’s bottom shielded these ancient wooden vessels from decay, keeping them waterlogged and intact. When wood has been submerged for thousands of years, much of its structural integrity depends on the water trapped within; archaeologists describe touching these canoes as feeling like handling a “sopping wet bagel,” where even slight drying can leave them warped, cracked, or crumbled.

“Archaeologists hypothesize that the canoes may have been intentionally cached in the water to prevent freezing and warping in the winter months and were later buried by natural forces over time,” says a news release from the Historical Society.

A Testament to Skill and Ingenuity

Each canoe began as a single, massive tree, typically white oak or cottonwood. Artisans expertly hollowed and shaped the trunks using stone tools and controlled fire, carefully balancing the vessel’s durability, buoyancy, and maneuverability.

“Even without finding the village, the discovery of these canoes and the tools found within the first canoe that was found, human-worked stone tools called net sinkers, reminds us that people have lived and worked alongside the lake for thousands of years,” said Rosebrough.

Tribal and Cultural Significance

For the Ho-Chunk and other Native Nations, these vessels are powerful, tangible links to ancestors whose ingenuity and lifeways shaped the region for thousands of years. Tribal leaders have emphasized that each canoe embodies not just the technical skill of its builders but also the lived experiences, cultural traditions, and spiritual beliefs passed down through oral histories.

“Seeing these canoes with one’s own eyes is a powerful experience, and they serve as a physical representation of what we know from extensive oral traditions that Native scholars have passed down over generations,” said Bill Quackenbush, tribal historic preservation officer for the Ho-Chunk Nation.

A Clue to Lost Villages

The concentration of up to 11 dugout canoes along an ancient shoreline suggests far more than casual loss or abandonment; it points to a sizable and enduring settlement nearby. Ongoing surveys and analysis, including radiocarbon dating, wood type studies, and underwater mapping, look for direct traces of habitations.

Traces like house remains, hearths, or tools, would confirm a substantial lakeside village or seasonal camp once existed here.

Indigenous Boat Storage Methods

During the winter months, it was common for canoes to be intentionally submerged in shallow waters and sometimes weighted with stones; this kept the wood waterlogged, preventing it from drying out, shrinking, or cracking in the cold, dry air.

“Either this practice of storing canoes for winter was carried out in roughly the same spot over generations – perhaps because of a living area nearby – or we are only seeing a window into a much larger site that might span much of the lakeshore,” said Rosebrough.

Are There More Treasures?

While no large structures have been excavated, researchers are optimistic that further exploration will reveal traces of houses or organized settlement, confirming Lake Mendota as a major hub of ancient Indigenous life.

“What’s eating away at me, honestly, is: Are there more?” Rosebrough said. “Is there a bathtub ring of canoes all the way around Lake Mendota? And that’s just one lake.”

More Than Just Canoes

While the canoes were among the most remarkable finds at this site, they weren’t the only ones. The first canoe lifted from the lake in 2021 was found with net sinkers, flattened, notched stones used to weigh down fishing nets, still aboard.

Stone tools have also been identified in the surrounding lakebed, hinting at the presence of nearby camps or villages. Archaeologists are actively searching for further evidence to learn about the communities that once lived there.

From Dendrochronology to Isotope Analysis

A few scientific tools were used to establish exactly how old these canoes are. Archaeologists collect tiny wood samples to determine species, but as the wood softens over millennia spent submerged, specialists at the USDA Forest Products Laboratory use microscopic cellular analysis to identify each type accurately.

Dendrochronology, or tree-ring dating, is sometimes used when preserved ring patterns remain, and strontium isotope analysis goes a step further. It examines the unique chemical signatures in the wood, which reflect the local geology where each tree originally grew.

Preserving Heritage

After their delicate recovery in 2021 and 2022, the two most intact canoes underwent an intensive conservation process. This involved soaking the waterlogged wood in polyethylene glycol to stabilize it, followed by freeze-drying to remove moisture safely.

Once fully preserved, these canoes will become the centerpiece of the new Wisconsin History Center, set to open in 2027.

Rewriting Midwest History

These ancient canoes are rewriting the story of the American Midwest, proving it was home to complex societies long before European contact. These finds prove that highly organized, skilled communities flourished for many generations. For Indigenous Nations, including the Ho-Chunk, these discoveries validate oral traditions and cultural memory, making visible their ancestors’ long-term presence and ingenuity.

“We are excited to learn all we can from this site using the technology and tools available to us, and to continue to share the enduring stories and ingenuity of our ancestors,” said Quackenbush.