There have been some pretty ambitious projects when it comes to exploring space and the planets within, but China and Russia have taken exploration to a whole other level. The International Lunar Research Station (ILRS), spearheaded by China and Russia, is set to feature a Russian-built nuclear reactor to provide reliable energy for a permanent base at the lunar south pole, with plans for completion by the mid-2030s.

The groundwork for the ILRS will be laid by China’s Chang’e-8 mission in 2028, which is expected to include the nation’s first astronaut landing on the lunar surface.

The International Lunar Research Station (ILRS)

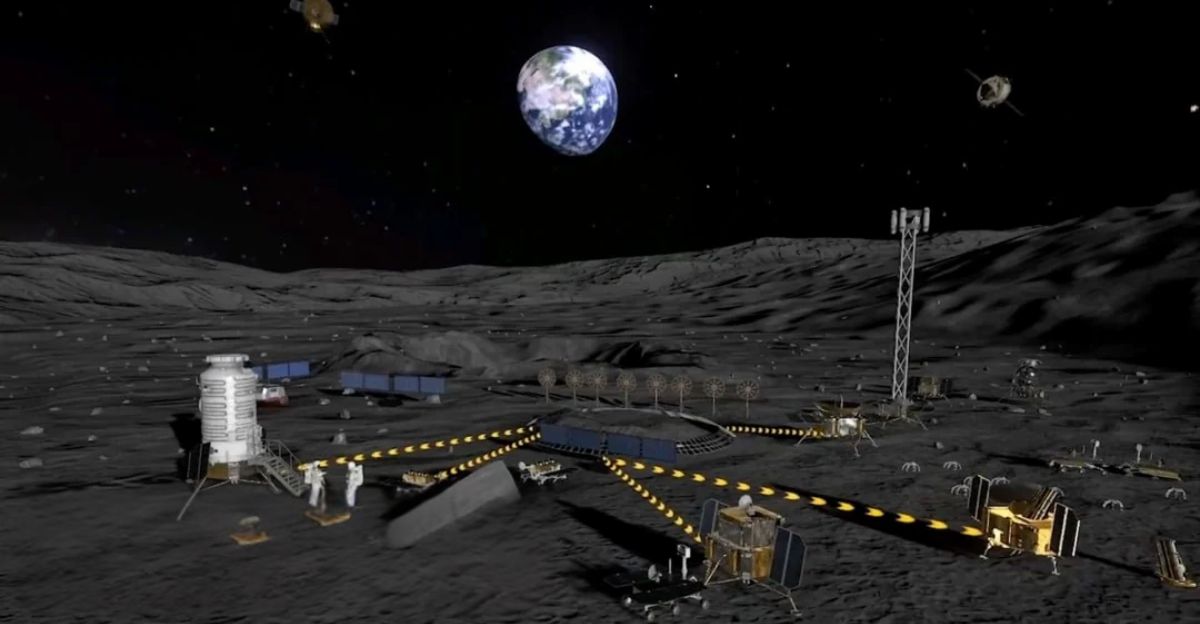

The station will be constructed in two main phases: the first, set for completion by 2035, will establish a basic research outpost at the lunar south pole, while the second phase, to be finished by 2045, will expand capabilities with a lunar-orbiting hub and advanced infrastructure for large-scale experiments and resource development.

“The station will conduct fundamental space research and test technology for long-term uncrewed operations of the ILRS, with the prospect of a human being’s presence on the Moon,” said Russia’s space agency, Roscosmos.

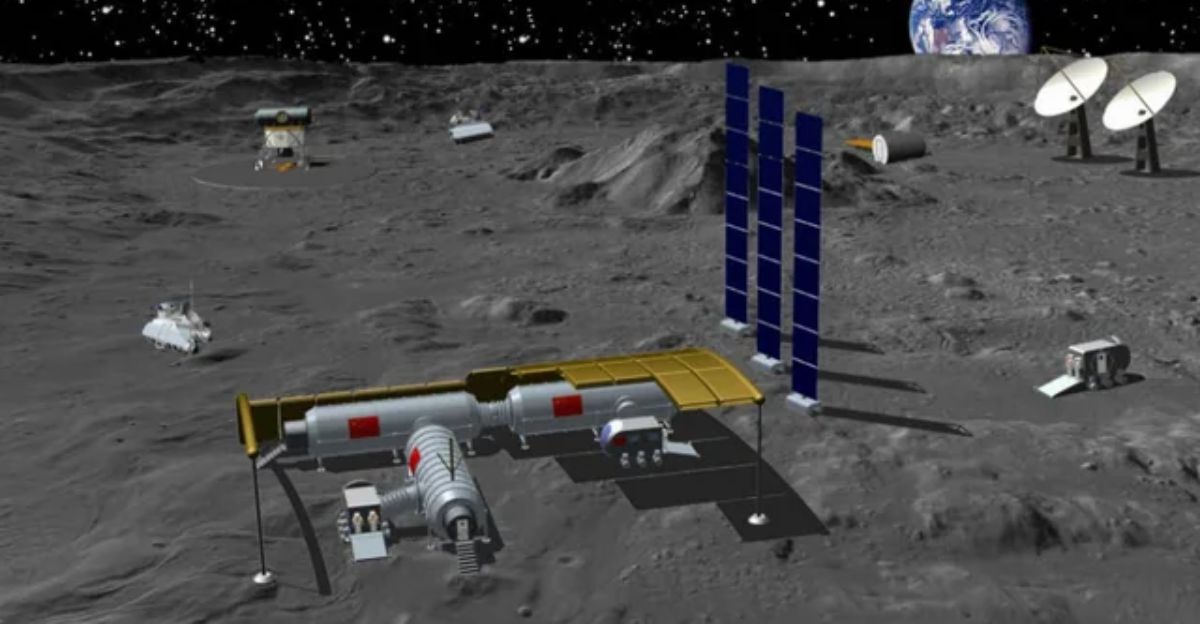

The Nuclear Power Plant

The International Lunar Research Station’s heart will lie at its core, the nuclear power plant. This power plant will be the lunar outpost’s primary and most reliable energy source, designed to deliver continuous power regardless of the Moon’s two-week nights or the challenges of solar energy in the harsh lunar environment.

The nuclear reactor is expected to provide around 40 kilowatts of electrical power for a decade or more, ensuring a stable supply for scientific instruments, life support, and base operations.

Timeline and Milestones

This extremely ambitious plan is set to happen in three manageable phases. The initial Reconnaissance Phase (2021–2025) is focused on lunar site selection and technology development. Missions like China’s Chang’e 4, Chang’e 6, and Chang’e 7, alongside Russia’s Luna 25, Luna 26, and Luna 27, all contribute to mapping, scientific surveys, and high-precision landing capabilities.

The Construction Phase (2026–2035) will see the deployment of key modules and the nuclear power plant, with Chang’e 8 launching in 2028 and subsequent missions. Finally, the Utilization Phase (from 2036 onward) will enable sustained research, crewed missions, and ongoing expansion.

Rivalry With NASA’s Artemis Program

It might not come as a surprise, but this program rivals NASA’s Artemis program to build an orbital station called Gateway. While both initiatives aim to establish a presence at the Moon’s south pole and leverage international cooperation, their approaches are entirely different. The Artemis program emphasizes crewed exploration, commercial partnerships, and a clear roadmap toward Mars, while the ILRS focuses more heavily on scientific research and robotic construction.

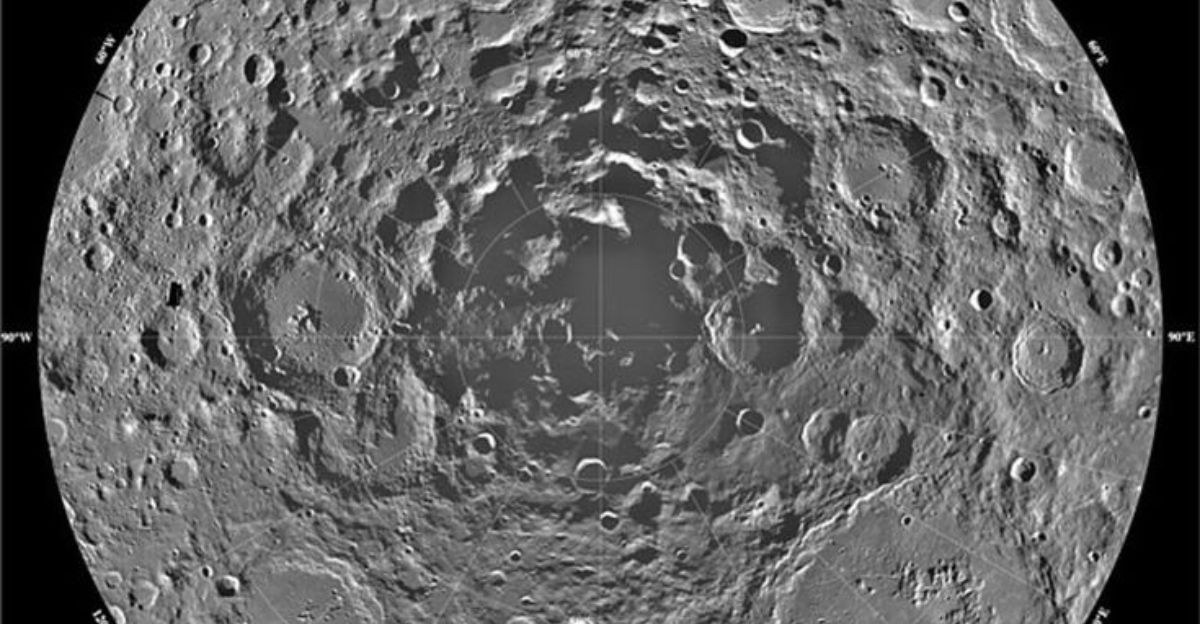

The Strategic Location

The Moon’s south pole is seen as one of the best places to plant roots for space exploration due to its permanently shadowed craters that act as natural cold traps, preserving vast deposits of water ice. This resource is critical for supporting life, producing oxygen and hydrogen for fuel, and enabling long-term human presence.

The south pole also has some of the best mountain peaks and ridges that enjoy near-constant sunlight for much of the lunar year, making it an excellent spot for solar power generation. Needless to say, this has become one of the most-wanted spots to set up a station for future space exploration.

Robots Lead the Way

If you’re planning on leading one of the most innovative builds of the century, ofcourse robots need to be a part of it. Advanced robotic rovers, 3D printers, and assembly machines are expected to prepare the lunar surface, erect habitats, deploy solar arrays, and integrate the nuclear power plant, minimizing the risks and costs associated with human labor in such a harsh environment.

“This is a very serious challenge…it should be done in automatic mode, without the presence of humans,” said Yuri Borisov, the head of Russia’s space agency. By relying on autonomous construction, the ILRS highlights the growing synergy between artificial intelligence, robotics, and space exploration.

International Collaboration and Membership

Since its joint launch by China and Russia in 2021, the ILRS has attracted participation from more than a dozen nations including Venezuela, South Africa, Azerbaijan, Pakistan, Belarus, Egypt, Thailand, Nicaragua, Serbia, Kazakhstan, and Senegal. Over 40 institutions globally have signed cooperation agreements, and the initiative continues to invite both traditional spacefaring nations and emerging space players to contribute at various levels, from concept studies to mission execution.

China’s “555 Project,” sets ambitious targets: to invite 50 countries, 500 scientific institutions, and 5,000 researchers to collaborate on the ILRS, creating one of the most extensive and diverse scientific networks ever assembled for a space endeavor.

Technological Challenges and Innovations

While technology is taking the lead in this entire project, there are a few challenges that need to be overcome. These challenges include developing robust autonomous systems capable of operating in the harsh lunar environment. The integration of nuclear power requires breakthroughs in reactor miniaturization, radiation shielding, and safe deployment to ensure both crew safety and environmental protection.

“It will also include lunar-Earth and high-speed lunar surface communication networks, as well as lunar vehicles like a hopper, an unmanned long-range vehicle, and pressurized and unpressurized manned rovers.” said Wu Yanhua, the chief designer of China’s deep exploration project.

Political Dynamics and Space Diplomacy

By partnering with Russia and rallying a growing coalition of nations, China is leveraging the ILRS to expand its geopolitical influence, much as it has with the Belt and Road Initiative, offering developing countries a chance to participate in a prestigious space project and gain technological and diplomatic benefits.

As space becomes a new arena for geopolitical competition, the ILRS is a way for China and its allies to challenge the existing U.S.-centric space order.