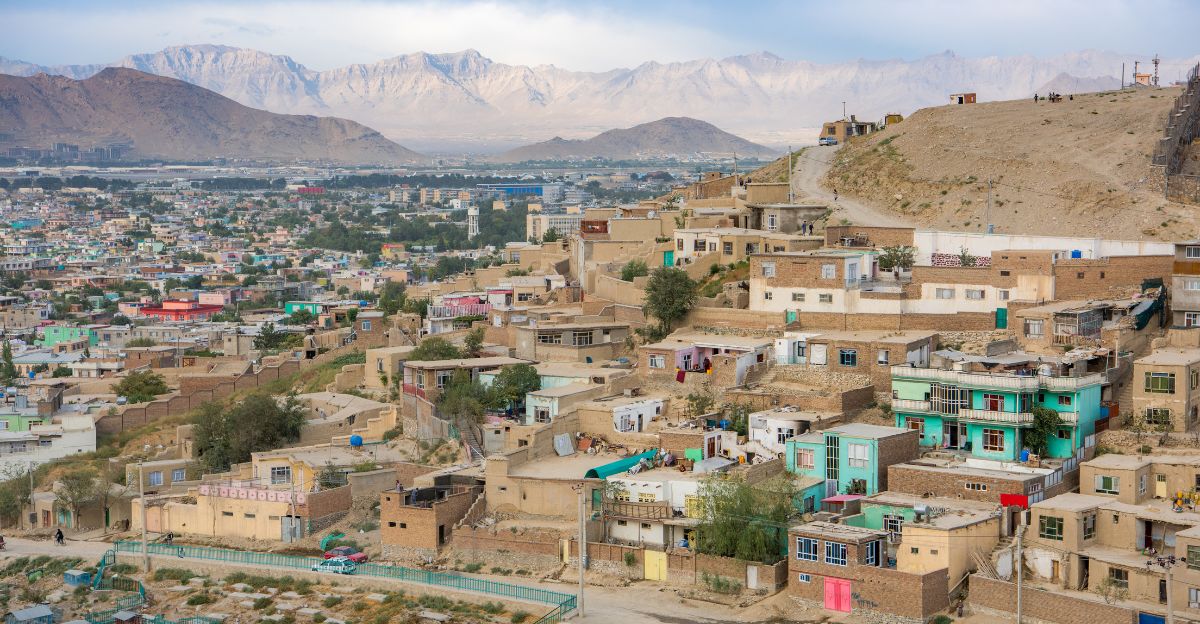

If you’re spending a lot of time reading headlines and following the latest news, it might seem like the world is heading to its bitter end soon enough, and titles like these just make it more likely. Well, believe it or not, in the 21st century, Kabul is poised to become the first capital city in modern history to face a complete and imminent dry-out.

For Kabul’s residents, the struggle for every drop of water has turned an occasional hardship into a relentless routine, with families sacrificing basic needs to secure limited supplies. What does it mean for this capital city, and could others be next?

The Daily Struggle for Survival

Every day in Kabul begins with uncertainty and urgency, as families race to secure even minimal amounts of water for drinking, cooking, and bathing. People wake up at dawn to stand in line and wait for water tankers to provide them with the water they need, with each ounce coming at a steep price that forces many to choose between buying water or food.

Wells have run dry, and women and children wander the city with buckets in hand, sometimes denied even a small share by equally desperate neighbors. For those without the means to dig deep private wells, dependence on costly tanker deliveries, public pumps, or the goodwill of others has become the norm. “We don’t have access to (drinking) water at all,” said Raheela. “Water shortage is a huge problem affecting our daily life.”

Water Quality, Not Just Quantity

Not only are residents facing water scarcity, but much of the available water isn’t safe enough to drink. Up to 80% of the city’s groundwater is contaminated, tainted by sewage, industrial runoff, and hazardous chemicals like arsenic and nitrates, making it unsafe for consumption.

Wells that still yield water often deliver foul-smelling, discolored, or visibly dirty supplies. In many districts, harmful bacteria and toxins have rendered water unfit for basic household use. Water quality assessments repeatedly surpass World Health Organization safety thresholds for critical indicators, and even families who dig private wells are frequently exposed to dangerous levels of salinity, heavy metals, and pathogens.

How Did It Come to This?

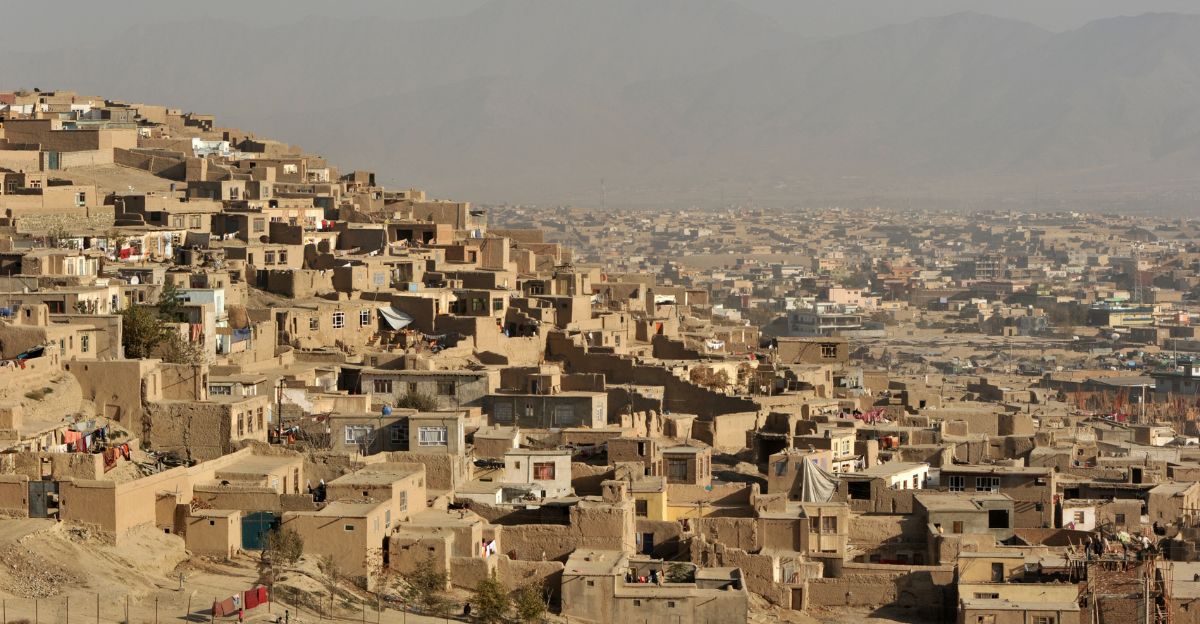

Kabul’s descent toward “day zero” results from a perfect storm of overlapping crises. Rapid, unplanned population growth has transformed Kabul from a city of about one million in 2001 to over six million today, intensifying the demand on its fragile water supply. Urban sprawl, booming construction, and more than 100,000 unregulated borewells have driven groundwater levels down by 82-98 feet in just a decade.

“Decades of unregulated well-drilling have led to massive over-extraction and contamination of Kabul’s aquifers, while critical surface-water reservoirs like Qargha Dam operate at significantly reduced capacity due to sedimentation and lack of maintenance,” mentioned a report by Mercy Corps.

The Timeline for the Collapse

Kabul’s collapse isn’t as far away as it seems, as the current situation is only getting worse. Nearly half of household wells are already dry, and each year Kabul extracts about 44 million cubic meters more water than can be naturally replenished, double what is sustainable. This trajectory puts millions at imminent risk of displacement and has already pushed everyday survival to a breaking point.

Without rapid, large-scale intervention, the city faces a high probability of total groundwater depletion by the end of this decade. “If current trends continue, UNICEF projections indicate Kabul’s aquifers will run dry by 2030, potentially displacing 3 million residents,” said the report.

Collapsing Infrastructure and Governance

Despite four decades and billions spent on international intervention, most of the city’s essential water systems remain outdated or fundamentally broken. Only about 20% of residents are connected to the city’s unreliable piped network, with the majority forced to dig ever-deeper borewells or buy expensive water from tanker trucks.

Key infrastructure, like the central water treatment plant in Baghrami, has never operated at full capacity thanks to incomplete construction and lack of maintenance, and much of the city’s sewage flows untreated into waterways, further contaminating already depleted aquifers.

“Kabul’s water crisis represents a failure of governance, humanitarian coordination, water regulation, and infrastructure planning. It is also a harbinger of climate-driven urban collapse, and the coming decade demands an unprecedented effort to increase Kabul’s aquifer recharge and political solutions to revive frozen aid pipelines,” concluded the report.

Price Surges and Deepening Debt

The price of water, once a manageable household expense, has surged to unprecedented highs. Some families now spend as much as 30% of their monthly income to secure enough for basic needs, compared to only 5% before 2021. In districts like Khair Khana, weekly water bills can surpass those for food, and private tanker deliveries have multiplied in cost, with rates up to $5 per cubic meter.

As a result, over two-thirds of households have been pushed into water-related debt, relying on informal lenders who may demand interest as steep as 15–20% each month. “Everything depends on water. Without it, life becomes extremely difficult. If these petrol stations stop giving water, people will die of hunger and thirst,” Mohammad Agha, a Kabul resident.

Recent and Ongoing Humanitarian Efforts

Between January and March 2025, humanitarian partners reached 7.6 million Afghans with at least one aid form, prioritizing districts with the most severe needs and targeting water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) as a critical focus.

The United Nations and international NGOs like Mercy Corps and the Red Cross have actively expanded community water points, distributed safe-water containers, and repaired critical infrastructure like pumping stations.

Delayed Solutions for an Answer

Decades of fragmented management, regulatory gaps, and weak institutional coordination have left water regulation and infrastructure planning in disarray. Multiple government departments often work in isolation, resulting in overlapping responsibilities and chronic inefficiency.

Major projects to address the crisis have faced long-standing delays due to funding shortages, political instability, and stalled international aid. International sanctions and the freezing of billions in foreign funding after 2021 have crippled Afghanistan’s ability to maintain or expand its water systems, while the lack of private sector investment further delays large-scale initiatives.

What Happens Next?

With nearly 2 billion people worldwide already lacking reliable access to safe water, the relentless combination of climate change, rapid urbanization, and poor governance is nudging more cities toward the brink. The collapse unfolding in Kabul is more than a local tragedy; it is a loud warning to governments, planners, and citizens everywhere that the world needs to take care of water threats before it’s too late.

“Four out of five people lacking at least basic drinking water services lived in rural areas. The situation with respect to safely managed sanitation remains dire, with 3.5 billion people lacking access to such services,” the report’s executive summary says. “Cities and municipalities have been unable to keep up with the accelerating growth of their urban populations.”