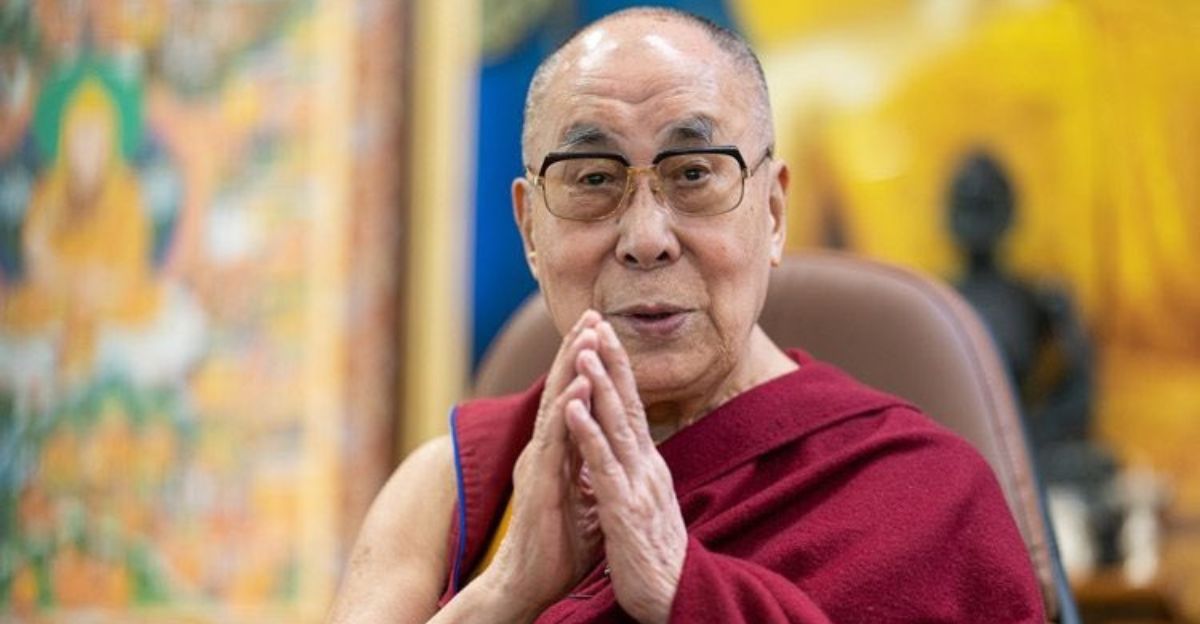

China’s claim that the Dalai Lama’s reincarnation “must follow Chinese law” is a calculated tactic to preserve social stability and national sovereignty, not merely a bureaucratic requirement. In order to prevent outside influence and maintain unity in a multiethnic country, the Chinese government insists that religious practices, including the choice of Tibetan Buddhist leaders, must comply with state laws.

Regulating religious succession is viewed as a means of thwarting the ascent of leaders who might oppose the state narrative or incite separatist sentiments in the framework of China’s larger policy of integrating ethnic minorities. China’s emphasis on legalism and centralized governance, where even spiritual matters are subject to state oversight to protect national interests, is also reflected in this policy.

Past Examples

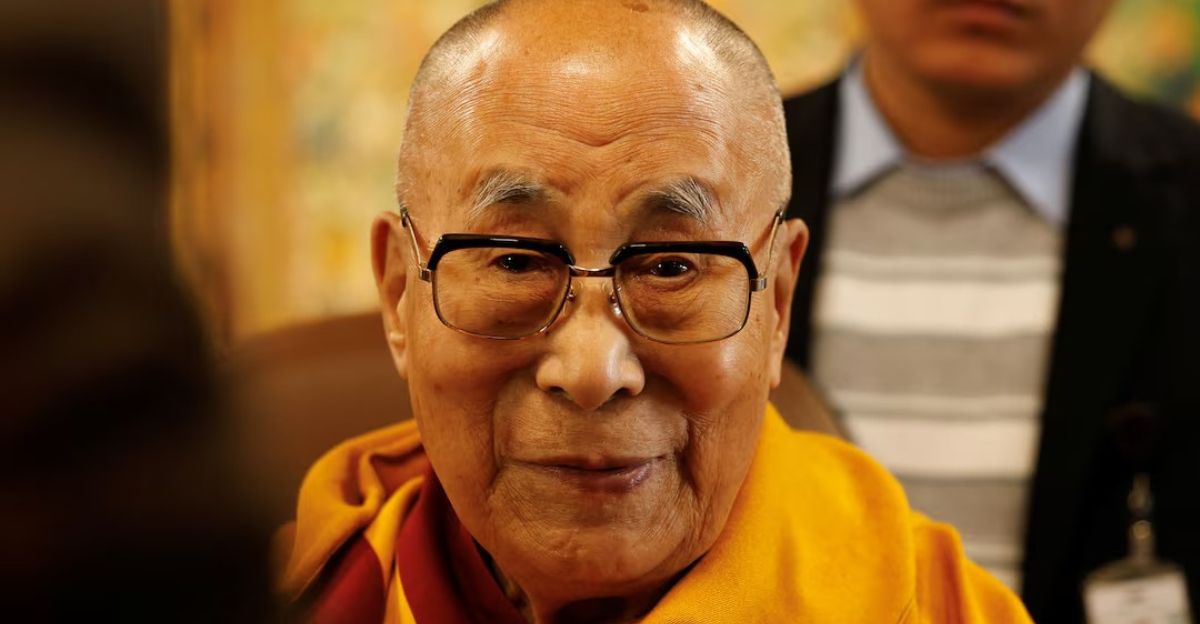

There is a centuries-old precedent for the state to get involved in the reincarnation of the Dalai Lama. In the 18th century, the Qing dynasty instituted the Golden Urn system, which required imperial authorities to approve the selection of high-ranking lamas, including the Dalai Lama. This system was created to keep Tibet, a region that has historically been susceptible to outside interference, free from power struggles and foreign influence.

This historical continuity is significant because it shows that the state’s involvement in religious succession is a revival of long-standing governance practices rather than a new imposition. Furthermore, the Golden Urn system was a reaction to Tibetan Buddhism’s factionalism, which threatened to destabilize the area due to rival religious groups. To avoid such divisions today, the state attempts to regulate reincarnation.

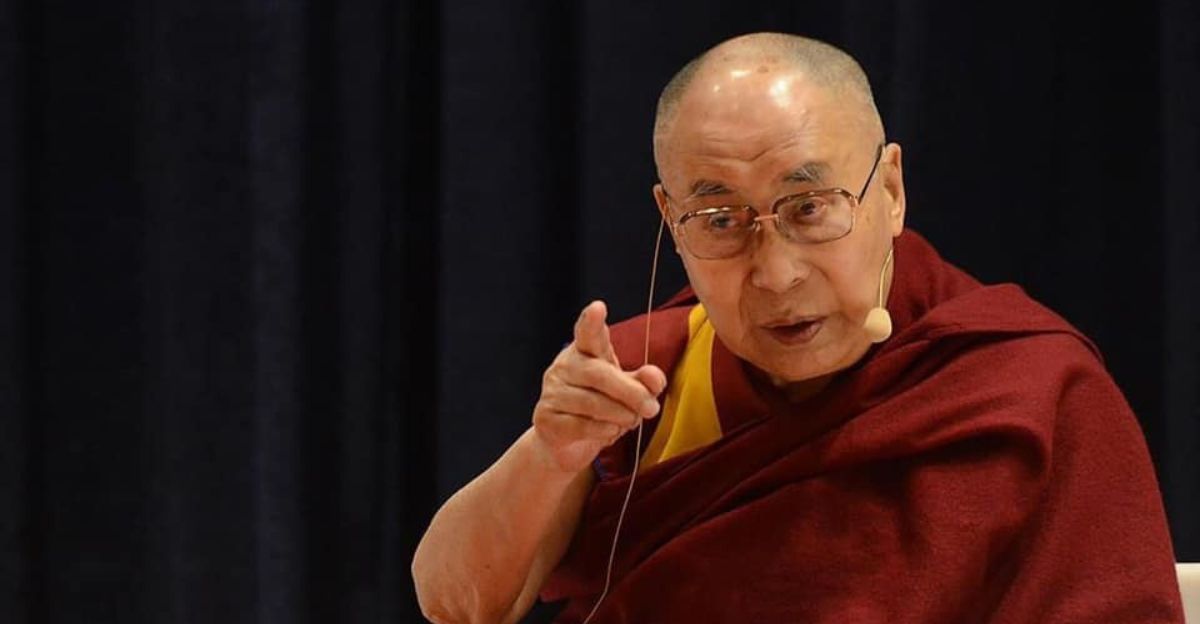

Law Enforcement and Order No. 5

The State Administration for Religious Affairs of China formally established the need for government approval for all reincarnations of Tibetan Buddhist lamas in 2007 with Order No. 5. By stating that unapproved reincarnations are “illegal and invalid,” this law essentially consolidates authority over religious succession. The policy is defended as a way to guard against false allegations and guarantee that religious organizations support national cohesion.

In order to prevent religious leaders from turning into political figures outside the state’s authority, Order No. 5 also represents China’s larger attempts to control religious practice through legal means. In order to bring religious teachings into line with socialist principles, the law’s enforcement mechanisms include public education campaigns, clergy training, and monastic monitoring.

Religion’s Sinicization

The foundation of China’s religious policy is the idea of “Sinicization,” which calls for all religions to conform to socialist ideals and Chinese cultural norms. According to the government, this procedure is necessary to promote social harmony and thwart religious extremism. Sinicization in the context of Tibetan Buddhism requires monasteries and clergy to uphold socialist ideals, encourage national unity, and support the Communist Party’s leadership.

State-approved religious curricula, educational programs for monks and nuns, and prohibitions on the influence of foreign religions all serve to enforce this ideological alignment. Beijing views Sinicization as a practical adaptation that maintains religious practice while guaranteeing that it promotes social cohesion, despite critics’ claims that it weakens religious authenticity.

Geopolitical Stability and National Security

Beijing’s authority over the Dalai Lama’s rebirth serves as a safeguard against separatism and outside meddling from a security standpoint. According to Chinese authorities, the Dalai Lama is a political figure with sway that goes beyond religion. Allowing an uncontrolled succession could make it possible for outside parties to use the organization to contest Chinese sovereignty in Tibet, like the Indian government or non-governmental organizations in the West.

The Chinese government is concerned that an externally selected Dalai Lama might serve as a focal point for international campaigns against Chinese policies or separatist movements. Thus, the reincarnation policy serves as a protective mechanism to protect interests related to national security.

State Sovereignty versus Religious Freedom

China’s policy is criticized for violating religious freedom, but this ignores the fact that no state permits religious authority to supersede national law without facing repercussions. For instance, the Vatican bargains with governments over the appointment of bishops; the monarchy in Saudi Arabia has strict control over its religious establishments.

Simply put, China takes a more methodical and explicit approach. Beijing is reaffirming the importance of state sovereignty, which is the foundation of the international order, by requiring that reincarnation adhere to Chinese law. It draws attention to the conflict between the rights of individuals or groups to practice their religion and the interests of the country as a whole, challenging the Western liberal presumption that religious freedom is unassailable.

The “Golden Urn” as a Template for Contemporary Government

The Chinese government has restored and modernized the Golden Urn system, which provides a distinctive framework for overseeing religious succession in a pluralistic society. China develops a hybrid model that strikes a balance between continuity and control by fusing state supervision with customary practices. Other multiethnic countries with comparable issues, like Russia with its Orthodox Church or India with its various religious communities, could adopt this strategy.

This blend of custom and contemporary governance offers a model for settling disputes between state power and religious liberty. Additionally, it exemplifies a creative approach to cultural heritage preservation that incorporates it into a legal framework that promotes national unity.

Second-Order Impacts: Disintegration and the Emergence of Rival Dalai Lamas

One acknowledged by Beijing and one by the Tibetan exile community, may emerge if China’s policy is successful. This situation would split the Tibetan Buddhist community, weakening the organization’s power and decreasing its ability to stir up opposition. The exile-backed figure may eventually lose favor abroad, while the state-backed Dalai Lama may eventually acquire legitimacy within China.

By undermining a possible source of cohesive opposition and making it more difficult for outsiders to use the Dalai Lama as a political tool, this division advances China’s strategic objectives. The dual Dalai Lama phenomenon may confuse followers and lessen the institution’s spiritual impact around the world. In addition to isolating the exile community, this division may hasten the integration of Tibetan Buddhism into China’s sociopolitical structure.

Third-Order Impacts: Social Engineering and Long-Term Integration

China’s authority over reincarnation may eventually make it easier for Tibetan Buddhism to become part of the national mainstream, weakening the sense of cultural uniqueness that motivates separatist sentiment. Beijing can cultivate a new generation of Communist Party-aligned clergy by progressively integrating Tibetan Buddhism with state ideology through the formation of religious leadership and doctrine.

The preservation of the Tibetan language, traditions, and customs may also be impacted by the slow assimilation of Tibetan Buddhism into Chinese ideology, which could result in a hybrid cultural identity. In the short term, this might ease ethnic tensions, but in a China that is modernizing quickly, it presents difficult issues regarding political integration versus cultural preservation.

Final Evaluation

In order to defend China’s policy regarding the reincarnation of the Dalai Lama, one must face difficult realities regarding sovereignty, power, and the characteristics of contemporary nation-states. Despite being contentious and frequently criticized as harsh, the policy has a logical foundation, the need to preserve national unity, stop foreign meddling, and unite diverse populations under a single set of laws.

China is not merely regulating religion by enacting laws pertaining to reincarnation; it is also carrying out a long-term plan to manage ethnic diversity, secure its borders, and project state power.