Archaeologists in west-central Poland have discovered two massive triangular mounds, each stretching roughly 650 feet and rising 13 feet high, during a routine archaeological survey of Chlapowski Landscape Park in Wyskoć.

Notes from Poland reported that these structures are at least 5,500 years old, making them about 900 years older than Khufu’s Great Pyramid in Giza. The age gap rewrites the timeline of Europe’s earliest monument-builders and hints at sophisticated engineering long before pharaonic Egypt.

But the question remains: What does this mean for our understanding of history and what else might lie hidden beneath Wielkopolska’s fields?

Farming Forebears

According to media reports, the mounds belonged to the Funnelbeaker culture, a Neolithic society spanning present-day Germany, Denmark, and Poland between 4300 BCE and 2800 BCE. Funnelbeaker communities introduced wheat farming, cattle herding, and Europe’s built some of Europe’s earliest megalithic monuments.

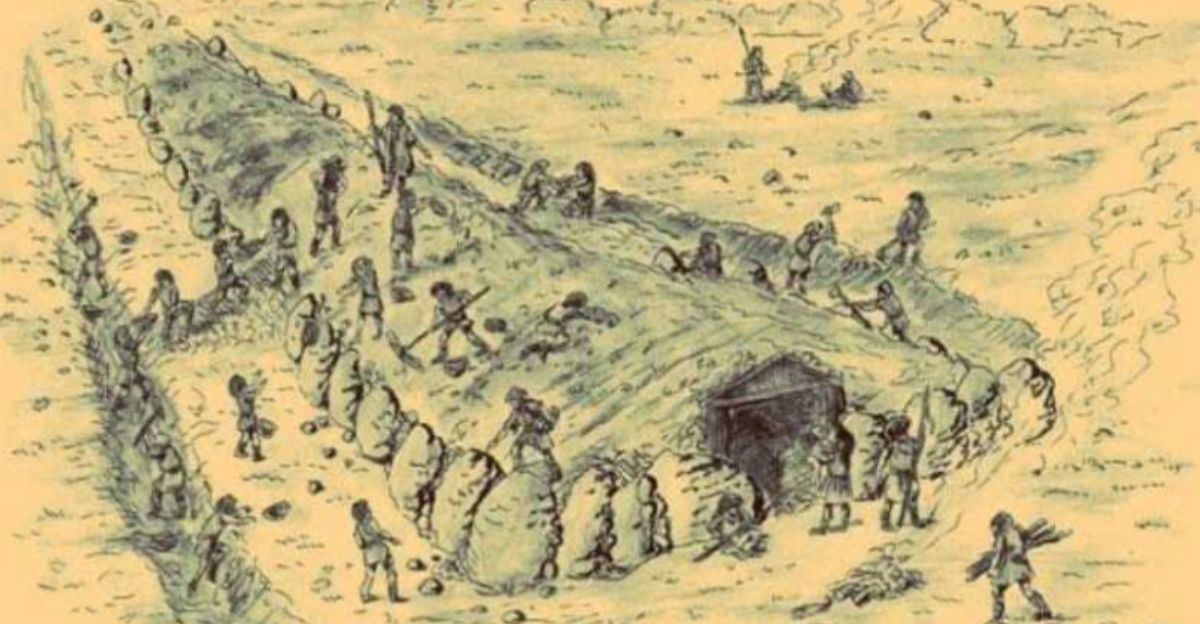

Long barrows, like those found at Wyskoć, were typically reserved for an elite burial—often a spiritual leader or clan chief—despite the culture’s otherwise egalitarian settlements. Scholars note that the barrows’ east-west orientation mirrors Funnelbeaker house plans, hinting at cosmological beliefs.

But what makes this find so important is that in studying these tombs, we may begin to understand how early farmers forged social hierarchies amid Europe’s dense primeval forests.

Hidden Lines

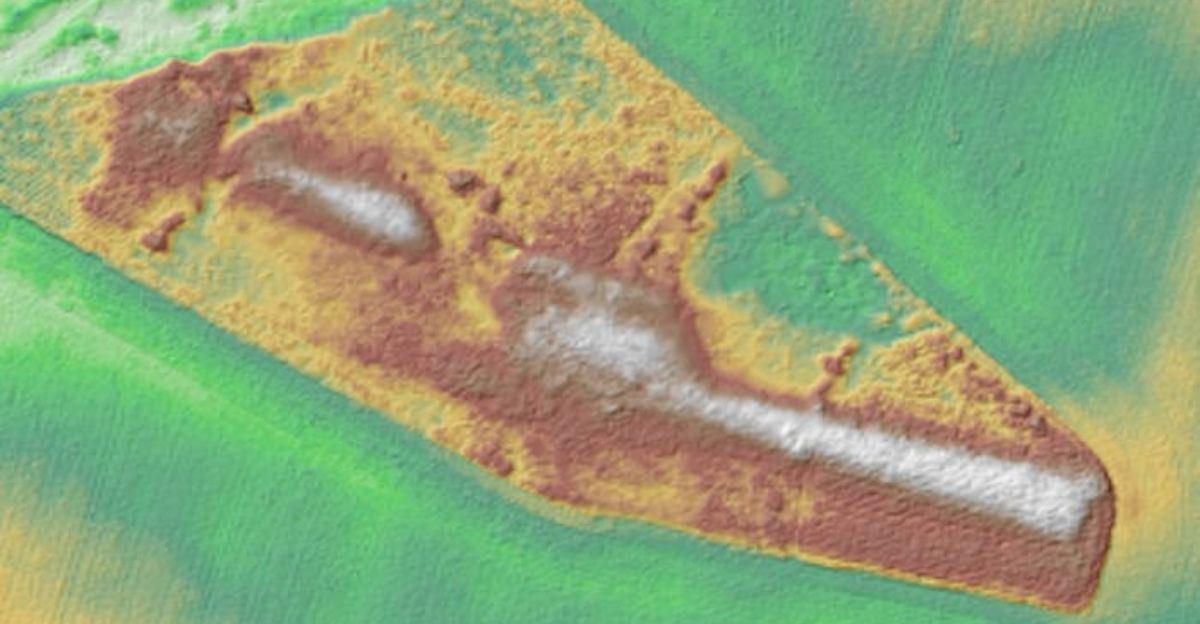

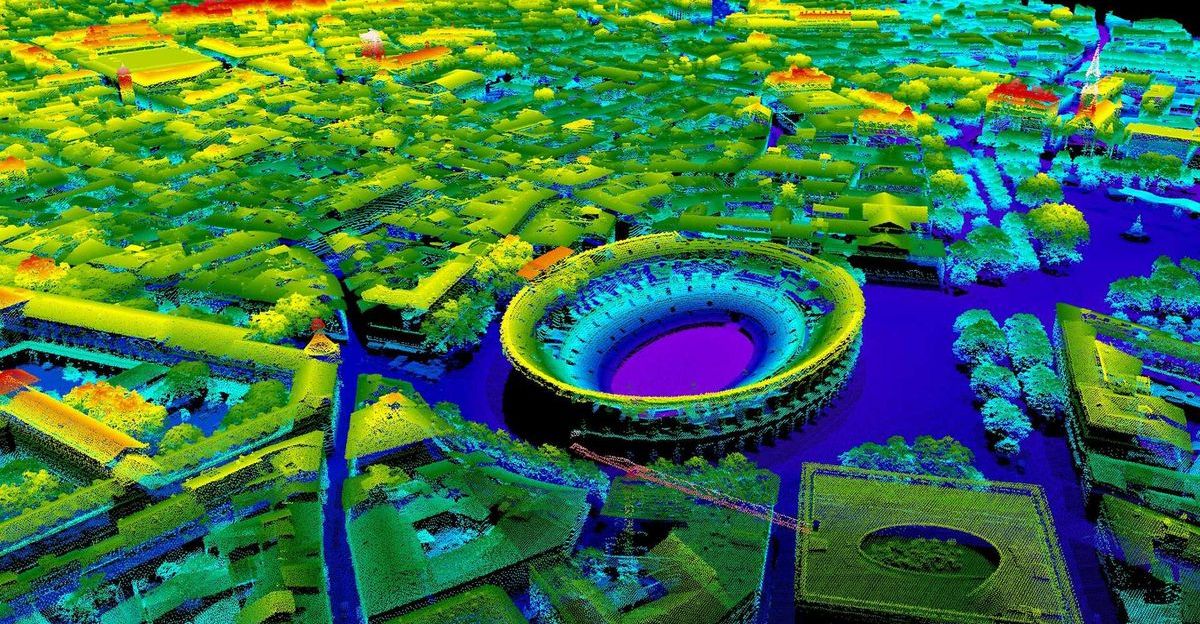

Popular Mechanics reported that the discovery began not with shovels but with lasers. Researchers from Adam Mickiewicz University used LiDAR surveys, flown over General Dezydery Chłapowski Landscape Park, that revealed two perfectly aligned trapezoidal outlines beneath the heavy woodland.

With the east ends wider and taller than the west ends, the triangular tail-like profiles are similar to Neolithic house designs. Further, excavators found that the builders covered the mounds with cobblestones and positioned massive boulders—some weighing 10 tons—at entrances, demonstrating sophisticated teamwork and tool mastery.

Park Reveal

When announcing this marvelous find, the Wielkopolska Landscape Parks authority posted drone photos of the two earthen giants on their social media, confirming the year’s most surprising European dig.

Lead archaeologist Dr Danuta Żurkiewicz says initial radiocarbon tests place construction between 3550 BCE and 3450 BCE, while Egypt’s most famous pyramid dates to about 2600 BCE.

A full excavation permit is still pending, but initial searches have already yielded a number of grave goods.

Findings Revealed

As reported by Artnet, initial findings uncovered scattered pottery shards, a polished flint axe and traces of a stone enclosure within the monuments, indicating ritual furnishings for a single high-status burial.

Though skeletal remains have likely decayed, researchers expect further digs to yield additional grave goods—possibly copper ornaments or opium-residue vessels—offering insights into Funnelbeaker cultural beliefs, craftsmanship skills and long-distance trade connections that flourished 5,500 years ago.

Local Stakes

Heritage officials predict the “Polish pyramids” could anchor a new cultural tourism corridor linking medieval Poznań with Neolithic sites farther north. Yet the mounds sit inside an active agricultural zone, where heavy machinery routinely passes by closely.

Landscape-park managers have imposed a temporary exclusion zone, but funding for permanent fencing and visitor paths is still needed. Further, regional planners weigh the benefit of job-creating visitor centers against local farmers’ fears of losing arable land.

Local officials say balancing preservation with farming remains a challenge as negotiations continue even as summer crops ripen around the dig.

Living Memory

Artur Golis, a conservation specialist surveying the site, grew up nearby. “Each generation built its own megalith, honouring the leader, priest, or shaman who guided them,” he told the Polish Press Agency.

For locals, that sentiment resonates; nearby villages still stage midsummer bonfires on ancient embankments that they call Łysa Góra—or “bald hills.” Residents of Wyskoć hope future tours will showcase both the tombs and current traditions, turning ancestral heritage into sustainable income.

But for now, they watch as excavation tents rise where their grandparents once grazed cattle, wondering what may emerge from the sandy soil.

Protecting Heritage

The find reignites debate over Wielkopolska’s resource corridor, which were heavily discuss when a lignite company, ZE PAK, planned new open-pit mines near Góry, 100 km east of the Wyskoć site.

Campaigners argue the 2025 discovery, one that might well be among Poland’s largest prehistoric monuments, strengthens the case for a protective buffer spanning all megalithic zones.

However, the debate continues as mining executives argue that energy security trumps ancient earthworks and promise “responsible extraction.” As a result, Poland’s culture ministry now weighs emergency listing of the Wyskoć mounds on the national monuments register.

Continental Context

LiDAR campaigns across Europe have identified hundreds of thousands of previously unmapped archaeological features, including many Neolithic barrows. A 2025 machine-learning survey published in Remote Sensing indicated to 1,200 potential barrows in Greater Poland alone, many hidden in commercial forests.

Researchers say that overlapping datasets could map the prehistoric landscape, aiding both archaeology and climate-era land management. The Wyskoć mounds thus join a continent-wide push to digitize—and ultimately safeguard—Europe’s oldest architecture.

Archaeological Legacy

These 5,500-year-old monuments fundamentally reshape our understanding of European prehistoric monumentality, demonstrating sophisticated engineering capabilities predating Egypt’s pyramids by 900 years.

The discovery has also shown that innovative LiDAR technology aids the advancement of regional archaeology, positioning Poland as a crucial center for Neolithic research.

Future excavations may reveal earlier prototypes, potentially pushing back Europe’s monumental construction timeline and providing unprecedented insights into early agricultural societies’ social organization and territorial marking practices.